The Year Ahead

What's coming up next in this space.

Hello again.

I hope everyone had a peaceful, restful holiday after the tumult of election season. Didn’t get quite as much rest as I’d planned, myself; as usual, there’s too much to think about, and too little time.

But we did have a wonderful snowy Christmas here.

Thing 1 and Thing 2 got a visit from Santa Claus; we trucked all across upstate New York, visiting lots of family; even got some sledding in, before an unseasonal thaw.

After months of anxiety, the much-hyped collapse of our democracy hasn’t materialized yet. Inauguration Day still looms. For now, the general mood among the anti-Trump faction seems to be one of grim resignation. Until something new pops off, it’s back to regularly-scheduled programming around here.

I picked up a new crop of subscribers during my electoral-politics bender in the final months of 2024. Newcomers might be confused by the sudden shift in tone. First of all, thank you to everyone who continues to take an interest in my work. Second—to clarify for new readers (and to reassure my regular audience)—while my interest in how the world works is relevant to mundane politics, as a general editorial principle, I Do Not Talk About Politics.

If you showed up for some hot takes on the election, I hope you won’t be disappointed; while I might occasionally touch on current events, I’m always trying to keep a watch on the bigger forces shaping those events.

Looking back at 2024

This past year felt a bit scattershot—and not just because of the turmoil around election season.

My first year on Substack was driven by fiction. While that experiment was successful, as far as completing some half-decent serialized short stories, I never quite got the hang of the medium. There is a way to make serialized fiction effective on Substack; from my experience, chopping up a larger story into little pieces doesn’t seem to be the best way1.

So I’d already started shifting away from my original purpose by the end of 2023. Looking back at my previous New Year’s post, I had intended to spend 2024 focusing on the book-length story that has been rattling around in my head for years now. (I also made some wild claims about “editorial restraint” and writing shorter posts. Ha.)

That obviously didn’t happen.

As a result, my output for 2024 was a bit of a dog’s breakfast. There was some worthwhile stuff in there:

Old Stones and Green Men was, far and away, my most successful post of the year. The idea of metaphysical conservatism and the need for re-enchantment is a concept in need of a good analytical framework; a respectful critique of this post by Sam Kriss offered a good point of contrast.

Similarly, the concept of metaphysical hyperobjects is something I hope to make use of in the future. I’m not sure if either my initial post on the subject or the follow-up series on Halloween took the idea far enough. But it’s a start.

My first real-world crossover with Dougald Hine—described in this essay—was another highlight of 2024; it was wonderful to meet Dougald in person and see the concrete output of his work in a real community (in addition to getting out of my own basement). Dougald has been doing the real work for a long time. He’s an excellent role model for an inexperienced keyboard warrior like me; watching him ply his trade was a great privilege.

Not bad, on the whole, but definitely lacking some consistent focus.

What’s Next

Part of the difficulty of doing this work is managing two different modes of literacy at the same time.

Applied metaphysics is already a stretch for most people. Writing in a practical way about concepts like hyperobjects and enchantment—without getting too poetic—is a challenge in itself. The customary academic tools for describing these things are useful, up to a point. But the logic of these ideas quickly drifts toward the outer edges of theoretical philosophy.

So I’m constantly ping-ponging back and forth, trying to describe something like orenda in an understandable way, without getting too deep in the weeds of academic language. If the description is too impressionistic, it’s easy to dismiss as New Age fluff; too philosophical, and it sails clear over the reader’s head anyway.

This is easily illustrated by looking at the interest mentioned above: “how the world works.”

If I was interested in “how the world works” from a materialist perspective, the way would be straightforward. There might be some high-flying technical terms in need of some wrangling—but, nevertheless, the path is well-marked, and many people have already uncovered answers to the same questions.

Once you step off that path, though, you’re immediately hacking through the undergrowth on your own.

In some cases—rather than being helped along with established trail markers—it can feel like you’re actively discouraged from exploring in certain directions. Particularly in English, the language itself is constrained in ways that make some ideas almost impossible to define.

Stepping off the path means confronting questions like this: what do we mean when we say “the world,” anyway?

And when we describe how it “works”—whatever “it” is—what functions do we include in that description?

Right away, a few important lines of inquiry branch off from that one sentence; I’m hoping to follow some of those over the next twelve months.

As always—this comes with the disclaimer that I am an autodidact, teaching myself philosophy in order to define these ideas. This terminology is all informal, and subject to misuse, contradiction, redundancy, and basic stupidity.

I. Phasmatopia Revisited

I’m always coming back to the idea of “phasmatopia” because I think it serves a useful analytical function.

Defining that function is one area in which the English language seems deliberately resistant. Cosmology is a term fenced off by materialist science; supposedly, it refers to the study of “the visible universe”—which leaves people who are interested in studying additional, invisible universes at loose ends.

Cosmology is something worth taking back from the scientists. It’s a container for some big questions: what exists? How do we know what exists, and how do we know what we know? Perhaps most importantly—what should we do about it?

Those questions can sound like trivial what-ifs, without a larger container to hold them. But they are immensely important: if the world is different than what we assume “the world” to be, then the answers to those questions will be radically different. How we know what we know, what we know to exist, how we should conduct ourselves based on that knowledge—these are all vital responses to “the world” that affect our survival, both as individuals and as a species.

And if “the world” is artificially defined in only one way, our range of possibilities is restricted.

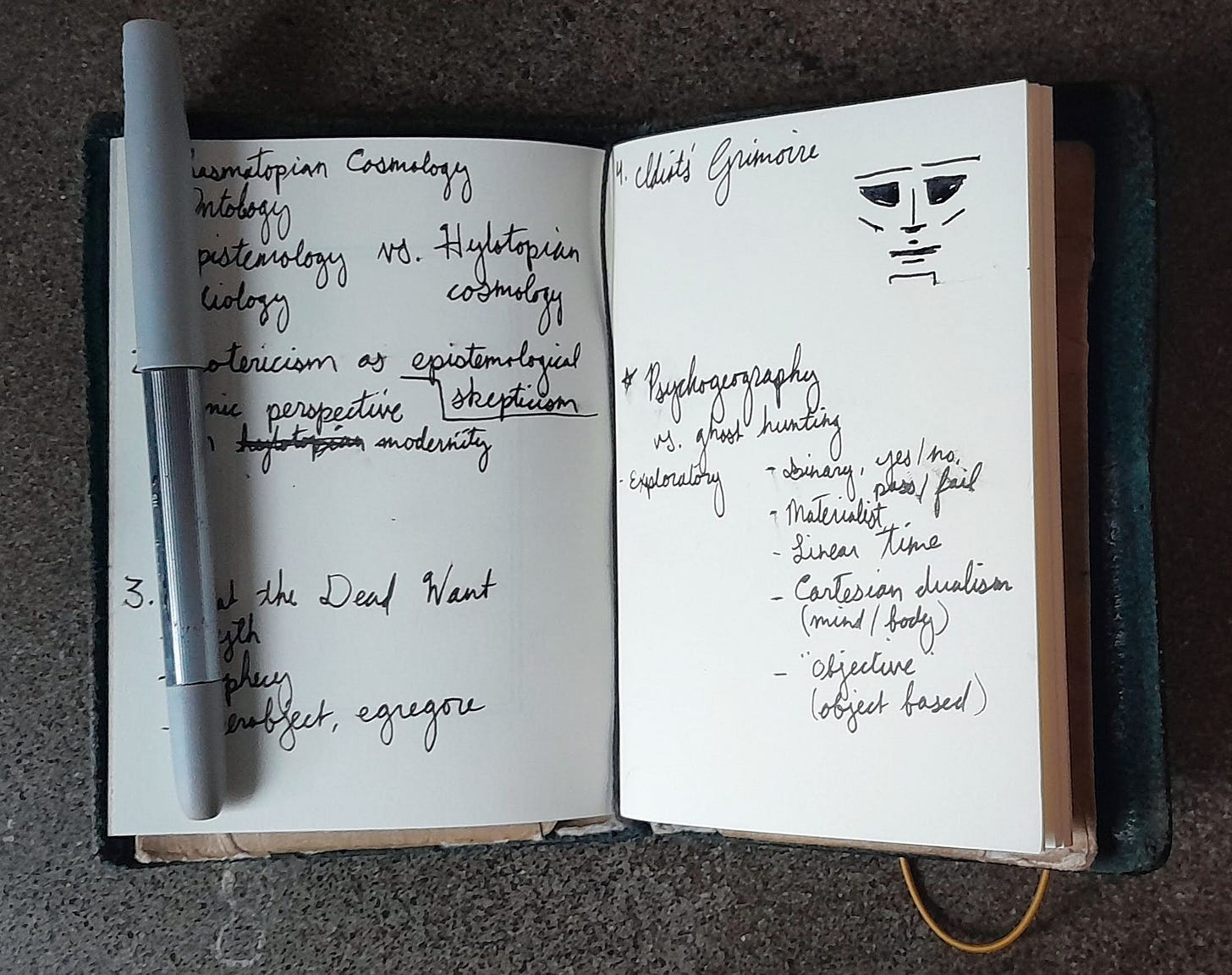

A phasmatopian cosmology presents a possible alternative, with its own perspectives on ontology, epistemology, and axiology; I’m looking forward to developing that more purposefully in the coming year.

II. Esotericism

If a phasmatopian perspective exists outside of a universalist2 cosmology, then esotericism is a particular slant on what we can know and understand from within it.

This gets messy quickly.

Universalist cosmology presumes that there is a single, unified, objective reality. Knowledge about that reality is generally assumed to be unrestricted. If we look at most of the standard Western philosophical models, there is no question about whether true knowledge is freely available; the differences are in the interpretation of those truths, and how we can best define what we know to be true.

I think this is one area in which science hasn’t fully escaped its monotheistic roots. The a priori assumption is that God wants us, as His subjects, to understand Creation, and freely grants us all the necessary tools to do so. Science got rid of God, but kept the axiom that there is a single source of Truth, which can’t be hidden from diligent inquiry. What was once God’s Truth is now Universal Truth, but it’s still treated the same way.

Esotericism, as I’m using it here, takes a skeptical stance toward the availability of truth. Modes of inquiry like empiricism and rationalism—the tools of Western science—aren’t reliable if knowledge about reality is being actively restricted.

This may sound conspiratorial, but that in itself is interesting: why should there be a taboo around the idea of conspiracy? Why should we be discouraged from wondering about hidden knowledge—or, for that matter, about the providence of knowledge understood to be universal? Why should we assume that all people have equal access to the Truth, as if it’s a natural law?

Esotericism overlaps with phasmatopian cosmology because, historically, many understandings of “the world”—particularly those we generally refer to as “indigenous”—have been suppressed, because they didn’t agree with the cosmological project of modernity.

Other cosmologies represent esoteric knowledge: those worlds are protected within a circle of understanding by the people who recognize them. Their existence is denied or obscured by the people within the circle, and also by people outside: knowledge about those worlds is regulated based on its usefulness, for insiders and outsiders alike, and not by its relation to absolute Truth.

There is a whole epistemology bound up in this deliberate regulation of knowledge. It’s another case of a concept hidden by opaque language—something hard to talk about, because it’s not supposed to exist, according to the dominant cosmology.

Contrary to the ethos of universalist science, the world isn’t discovered. It’s created by the construction of truth and falsehood. Esotericism—the study of secrets, of what is allowed to exist and what is denied—gives us a negative template for understanding other possible worlds.

III. Myth, Prophecy, and Zombies

Those first two topics could probably fill a book or two by themselves (and maybe they will) but they’re just part of building the airplane while it’s taking off3. I’m hoping I can use those two perspectives to flesh out one particular line of inquiry: the book project described in this post, looking at the cultural phenomenon of zombies as a mythic outburst rather than just an entertainment product.

Again—this gets messy quickly.

We can’t easily talk about myth and prophecy from within the constraints of a universalist cosmology. Most English-speaking people have probably never considered how their epistemological assumptions—what they know, and how they know what they know—are based on a specific understanding of linear time. Or, for that matter, how something like Rupert Sheldrake’s theory of morphic resonance is discounted because it clashes with our idea of “the natural world.”

These assumptions are specific to a universalist perspective, and simply aren’t relevant in other cosmologies.

For example—in a culture that recognizes the reality of prophetic knowledge coming form metaphysical entities like the Dead, the omissions we take for granted would be almost impossible to ignore. Something dismissed as cheap entertainment by one culture becomes much more urgent and ominous with the proper framing. The zombie phenomenon might be one such case.

IV. Psychogeography

But wait! There’s more!

I’m still tinkering around with a possible audio project—a reason to get out of my Fortress of Solitude, away from the keyboard, and counteract all this abstract theorizing with some fresh-air exploration.

Based on all the foregoing assumptions about a phasmatopian cosmology, there are some interesting ways of interacting with a local landscape that don’t fit neatly into the customary categories.

While psychogeography is not a new thing, many of its public advocates seem bound by mainstream ideas of respectability. The same goes for parapsychology and what’s typically referred to as “ghost hunting”: they’re pseudo-scientific, in the sense that they’re trying to use the tools of empiricism to justify something that doesn’t fit within a universalist cosmology.

I love the Hellier investigation (mentioned in a previous post) because it documents the kind of phasmatopian psychogeography I’m interested in. The Hellier team seems largely unconcerned with any kind of proof that would satisfy (universalist) skeptics. They’re just doing it for the love of the game, willing to follow the trail wherever it leads.

What I find frustrating about the project (so far, based on the two seasons available as of this writing) is the inability to fully embrace that perspective.

The team habitually falls back into the mindset of paranormal investigators: treating their subject as a singular phenomenon, or as a trail of breadcrumbs with a verifiable beginning and a definite end. In spite of their open-mindedness, the Hellier team often behaves like the gang from Scooby Doo, expecting to pull the rubber mask off one specific villain. While they’re not chasing definitive proof, they’re still approaching their project as an investigation—a problem to be solved, rather than an exploration of the (super)natural contours of a landscape.

There’s so much potential in expanding that methodology into multiple dimensions: mapping many different overlapping streams of phenomena throughout an area, without getting stuck on one specific puzzle, or bogged down with collecting data that skeptics might find appealing. This approach would be much more impressionistic (and might not yield an award-winning documentary) but it would be a map of a landscape—a representation of a total space, rather than just a succession of clues in a thin case file.

Regardless of whether the Hellier investigation continues to produce results, it offers a great model for a different kind of psychogeography, which I’m hoping to expand in my own neck of the woods.

Big dreams.

Then again—I’ve got a whole twelve months to fill.

Wish me luck.

Thanks for all your support. Here’s to a prosperous new year for my readers, and for everyone in the Substack neighborhood.

If I had to go back and do it over (and maybe I will in the future) something like microfiction seems better-suited to serialization and the constraints of the medium. A series of self-contained stories could work really well: gradually developing a group of characters and building a world through a collection of vignettes, rather than a start-to-finish narrative broken up into snack-sized portions. Maybe that’s the project for 2026 (or maybe sooner, if this is the year I finally manage to clone myself).

Once again, having to make up terminology—what do you call the cosmology that our modern, capitalist, techno-utopian culture occupies? There’s not really a name for it, because it’s not supposed to be one of many: it’s supposed to be the only one, objective reality, “the way things are.” In the English-speaking world, we’re discouraged from thinking comparatively about our own cosmology. Similarly, Yahweh became “God” when it was decided that he should be the only one in the cosmos; at a linguistic level, people were discouraged from thinking about other gods as Yahweh’s peers, or from remembering what Yahweh used to be in a monolatrist culture. This gets into the epistemology of esotericism: it’s a very clear example of the world being altered through a restriction of knowledge.

Personal note to Rhyd Wildermuth : I really am working on it, I promise.