The Night-Thinned Veil, Part 1

Halloween as a case study for hyperobjects, symbolic interfaces, and metaphysical conservatism.

In my previous post, I came up with a possible formula for enchantment, and applied it to the Hastings Traditional Jack in the Green as described by

.This time, I’d like to apply the same formula to a more familiar symbolic interface—Halloween—to see what it can tell us about the pitfalls of metaphysical conservatism.

Here again is my hypothetical formulation for enchantment:

Enchantment is the process of creating and sustaining a symbolic interface that corresponds to one or more hyperobjects, in order to generate participatory consciousness.

As described in the previous post, hyperobjects are metaphysical phenomena that are too massive and too weird—and, consequently, too terrifying—for humans to fully comprehend.

The universal force of gravity is the mundane example I used before: when we break gravity down into specific instances, or into mathematical formulas, we can start to wrap our minds around it. But when we try to imagine the totality of gravity, the vast weirdness of the physical universe in every possible spatiotemporal dimension, we experience a kind of cosmic megalophobia.

Symbolic interfaces—words, icons, avatars, mudras, music, dances, rituals—act as buffers for this reflexive horror. We can artificially humanize some of the local aspects of these massive hyperobjects to build a relationship with them. Whether the relationship is based on influence or acceptance, it keeps us from losing our psychological footing when we’re confronted with something that is unavoidable, undeniable, and psychically overwhelming1.

Death and participatory consciousness

Death is a hyperobject2. It’s probably the most consequential hyperobject, from a human perspective, because it drives the fear that makes all other hyperobjects difficult to deal with. Confronting these immensities of time and space through the window of our tiny, fragile bodies is terrifying.

On the reverse—participatory consciousness allows us to override that fear by identifying with the world outside our bodies. An expansive consciousness helps us deal directly with Death, as well as the fear inspired by the mortal danger that hyperobjects represent to humans.

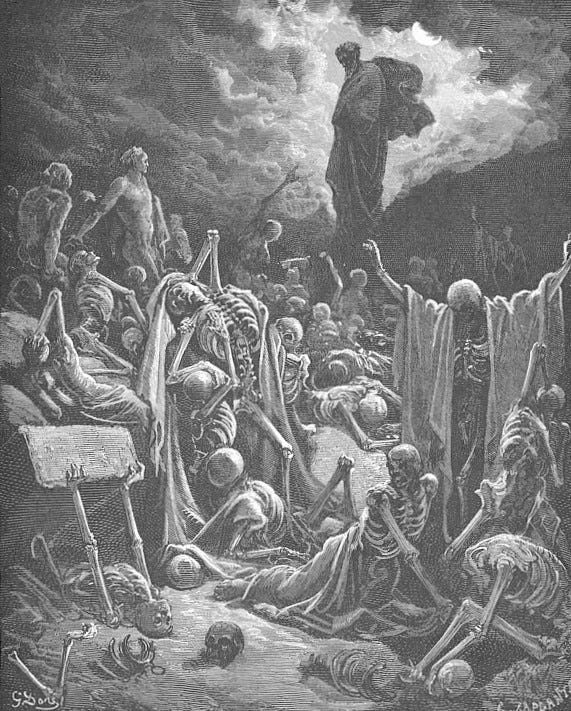

It would make sense, then, for most of our symbolic interfaces to be keyed for Death. And this is obviously the case. Going all the way back to the first evidence of human funerary behavior, 115,000 years ago (or more?), humans seem to have arrived early at the conclusion that Death was a transformation, rather than a definitive end. The earliest foundations of magic and religion were developed to navigate the corridors of the afterlife.

Paleolithic shamans pioneered the metaphysical praxis of using Death as a doorway. Having one foot in the afterlife was a minimum qualification for the job. In traditional cultures, people who had near-death experiences were automatic candidates. Shamans routinely used trance-inducing technology that would put them into a deathlike state: ecstatic dance, self-mortification, and toxic substances, among other methods. When they returned to their bodies with esoteric knowledge and unusual abilities, they cemented the idea that people who went through the doorway and stayed on the Other Side could act as spiritual patrons.

Mindful handling of the dead—empathizing with the non-living—using participatory consciousness to identify with the Dead, and with Death itself—was recognized as an obvious way to grease the skids in these relationships.

It’s also necessary on a purely psychological level. For people with bodies, trapped in linear time, maintaining the awareness that biological death is not The End has always been difficult. This is an enchantment that wears out quickly. Pain corrodes it. Seeing all the horrible ways that life can end, all the suffering, all the lights extinguished that will never be lit again—it’s easy to lose the sense that there is a wider world beyond our physical vulnerability.

Keeping that sense alive in the human body requires regular—very regular—encounters with Death as a hyperobject. Not the experience of individual deaths as immediate tragedies, as pain and loss, as a mechanical breakdown, localized in physical bodies. Humans need contact with the greater Mystery that phases in and out of our dimension, taking consciousness up into something beyond the present world.

This isn’t just religious eschatology. It’s not some distant, abstract faith in an Afterlife that we only glimpse at the very end. For many people, in many cultures throughout human history, this transit is a regular commute on their way to work.

We forget this, and need to be reminded of it.

To be fully human—to not be chronically terrified by the fact of our own existence—we need to stretch our awareness out across the River. Repeatedly.

Even at the risk of falling in.

This is the most radical form of participatory consciousness. For a person to reach across that divide before the final departure—to reel out the tether that holds the spirit in the body, as far as it will go, and then wind it back in—means deliberately surrendering their humanity. Lowering every spiritual defense in order to identify with Death, against every survival instinct hard-wired into the physical body. Knowing that the process might be irreversible. Trusting to be brought back to life, with no guarantee.

Death and symbolic interfaces

To do this difficult and dangerous work, the symbolic interfaces in these rituals are more than just aesthetic: they act as guardrails, making the experience relatively safe (but not too safe) and providing a handhold for the traverse between worlds.

This is, in one sense, consistent with Sam Kriss’s formulation of “just doing stuff,” insofar as these are practical inventions with a definite purpose. These interfaces—the avatars, the symbols, the language, the rituals—were bred for performance. They represent successive generations of guided evolution, form matched with function in a specific environment, rather than some idealized shape recognized as culturally or historically “correct.”

Like working dogs, the beauty of these symbols were originally a byproduct of their ability to do a task well3; their aesthetic value is incidental.

However—that also means the caretakers of these symbolic interfaces aren’t “just” playing with form, and celebrating novelty for its own sake. A poorly-designed symbolic interface could mean a bad connection, preventing both the operator and her tribe from getting the full benefit of contact. Or it could mean the operator falling forever out of the human world, shattering the mind and killing the body. Or, in some cases, it might let an opportunistic entity follow the returning operator back into the material world4.

These symbolic interfaces serve several functions:

The work of full-time seers, described above, is at the extreme end of the spectrum. The symbolic interfaces used for this work are designed to to take an operator’s spiritual body entirely into Death, as an ambassador, while keeping the physical body alive.

Some adulthood ceremonies could be viewed as intermediary forms of shamanic encounters. Adult business brings people into regular contact with Death as responsible parties—birthing, healing, caring for the elderly, hunting, slaughtering, warring—in a way that children are exempted from. It’s useful to mark the transition into adulthood by skimming along the surface of Death, without needing to perform the regular deep dives of professional seers.

There are symbolic interfaces for the diplomatic work of maintaining good relations with the Dead. Outside of war zones, there is no culture on Earth (that I know of) embracing a thoroughly reductive materialism and throwing the dead out with the trash. Even modern people retain a superstitious fear of the Dead’s displeasure. Beyond funerals, there are many rituals (both esoteric and exoteric) to keep the Dead in harmony with the Living.

At the most mundane level, there are symbolic interfaces to remind people of the inevitability of Death—to promote a familiarity with Death as a concept, and to ease their fears about its approach. Even in modern cultures, there are no atheists in foxholes, and very few firm materialists when it comes to letting go of our loved ones (or ourselves). This is the minimum level of assistance that a healthy culture can provide.

With this, we can start to evaluate the effectiveness of a particular symbolic interface in promoting these different modes of participatory consciousness, with Death as the hyperobject on the other side:

Does the symbolic interface support participatory consciousness with Death by resonating at a useful frequency and volume, neither too weak nor too strong?

If it fails to function—what vulnerabilities does it expose in the host culture?

How can the symbolic interface be re-enchanted, in order to restore its ideal resonance with the hyperobject?

That last point is the most urgent when it comes to modernity and the loss of participatory consciousness.

Animacy, Metaphysical Conservatism, and Appropriation

Metaphysical conservatism is what drives the resistance to re-enchantment; it’s particularly dangerous, because it’s a form of materialism that agrees with both secular and religious paradigms.

Modern institutions5 claim that cultural symbols are inanimate objects. While people’s relationships with these symbols might change and evolve over time, the symbols themselves are just containers for meaning. And, crucially, they are the possessions of the cultures that have a historical claim to them.

This materialist understanding of symbols has two important consequences:

The value of a symbol becomes quantitative, measured by how much meaning it has accumulated over time.

Members of a particular culture determine the correct usage of their symbolic interfaces in perpetuity—regardless of how the forces working through the interface choose to behave.

From this perspective, tradition becomes a form of preservation.

It’s the difference between keeping a chisel sharp—replacing it, if necessary, because the task is more important than the tool—and putting the chisel in a museum behind glass, so it stays sharp forever.

When symbolic interfaces are reduced to containers for the passive (anthropocentric) appreciation of meaning, the focus shifts away from the animate power they reference. Tradition stops being a way to maintain an effective metaphysical relationship. The human side of the interaction neglects the ongoing need to keep up with the dynamism of a hyperobject. It’s no longer a practical means of passing on what works: the continuous research and development of applied metaphysics, experimental results accumulated over centuries’ worth of trial and error.

Instead, tradition sinks to the level of mundane politics, as a way of asserting control over a cultural space.

Authenticity becomes enormously important. Historical pedigree turns into a source of conflict. Once disenchanted and fully materialized, newer symbols contain less value than older symbols. Older symbols, with the stamp of authenticity, are understood to hold a greater quantity of meaning. Groups must demonstrate ownership in order to maintain legitimate engagement with a symbolic interface. Undercutting the historicity of a symbolic interface, from a materialist perspective, means devaluing it as a container of meaning and weakening a group’s claim to legitimacy.

It’s very important to note that cultural appropriation and disenfranchisement are serious concerns. These represent genuine historical crimes that can’t be dismissed or diminished. Coachella Headdress Girl should definitely be held to account and publicly ridiculed.

But the way we think about these transgressions and how we police cultural boundaries could look very different, if we acknowledge that there are dynamic, unpredictable, animate forces behind these symbolic interfaces, which do not conform to materialist understandings of culture and authenticity6.

The bigger problem is not theft: it’s the ontological perspective telling us that the symbolic interface—the thing that can be stolen—is the primary source of value, rather than the relationship with the hyperobject it represents.

Coachella Headdress Girl deserves exactly zero sympathy for being an entitled cultural bottom-feeder who sees the world as one big photo booth, pre-stocked with props for her amusement. That kind of sincere cluelessness is expensive. If a person never has to worry about health care, or vacations, or which home to live in—they can afford to be the scapegoat for our culture’s spiritual crimes.7

But the real crime is ignoring the relationship that the symbol represents. These days, that judgment falls heavily on “insiders” and “outsiders” alike. Even for people with a genuine cultural connection to these symbolic interfaces, how many still recognize and maintain them as vital tools for spiritual survival? How many are still afraid—genuinely afraid—of the spiritual consequences that come from neglecting the old covenants?

If Coachella Headdress Girl is wrong for believing it’s “just” a fancy hat, and the only retort is “No, it’s their fancy hat”—if the only thing we’re afraid of is public censure from the Bureau of Cultural Appropriation—then how much have we already lost? How much can we hope to claw back by pillorying one annoying rich kid, when the stakes are so high8?

From the materialist perspective, a symbolic interface is more like a lawnmower than a dog. It’s an assemblage of parts to be possessed. If its owners choose to do so, they can leave it out in the elements, neglected, until it ceases to function, with no moral cost to the wider spiritual ecology.

Meanwhile, the animate understanding recognizes and requires re-enchantment, giving license for any group to adopt a cultural interface (or for a cultural interface to adopt a group) on the basis of a genuine, effective relationship with the hyperobject it represents.

This isn’t just an academic difference of opinion. Claims of metaphysical conservatism and the struggle over ownership can have serious consequences. If we don’t resolve these questions, whole communities can be left completely bereft of participatory consciousness. People are disenchanted, confused, and psychologically damaged by unmediated hyperobjects. This makes them irrational; they lash out in unpredictable ways.

From an animist perspective, all people suffer the consequences of neglecting these relationships: human and non-human alike, and the whole world along with it. We all have a shared obligation to figure this stuff out. That also means a shared responsibility to answer for our transgressions, regardless of which culture we belong to.

But according to the materialist rules of modernity, I have no grounds for critiquing a culture to which I don’t belong. I’m an Anglo-American mutt with no real religious background. My options are limited.

Out of respect for the rules as they’re currently constituted—Halloween is nominally a part of my culture. More importantly, the ways in which it might not be part of “my” culture represent some interesting and relevant contradictions. So we’ll tackle that as a case study in Part 2.

As I wrote before: Lovecraftian horror is a good illustration of exposure to hyperobjects without an effective symbolic interface.

If this feels too technical—too materialistic—we could also say that “Death is a Mystery,” with a capital “M,” to differentiate it from the Agatha Christie kind. The trouble is that modernity considers the whole idea of something fundamentally unknowable as an affront. There can be no Mysteries, because knowledge is power, and anything unknowable is also uncontrollable. Traditional cultures with an intact sense of participatory consciousness seem more tolerant of Mysteries; presumably, complete understanding isn’t a prerequisite for relationality, in the same way that it is for control.

According to this analogy, the symbolic interfaces that have been divorced from their original function and reduced to superficial aesthetics are like those purebred show dogs with congenital defects. Or the Hapsburgs.

There is no shortage of folkloric accounts that describe accidental possession or haunting as the result of a faulty symbolic interface. The most interesting account I’ve come across recently is

’s DPT experience in Breaking Open the Head:I saw a brand-new and extremely detailed demonic realm swirl before me in cobalt, scarlet, purple gossamer hues. At moments there seemed to be some incredibly elegant yet violently orgiastic party taking place, with beautiful females in evening gowns and men in Edwardian topcoats, in the spacious parlors of a huge and opulent mansion. At other times there seemed to be bat- or butterfly-winged creatures—long and quivering antennas, velvet coats and emerald eyes, stiletto talons—rising into otherworldly skies, wandering futuristic cities. I had an impression of tremendous vanity. “I” was a mirror for the DPT beings to admire themselves… Not only was it suddenly obvious that there was such a thing as a soul, it was also clear that I was in danger of losing mine permanently. [Later] the trip was starting to wind down. In a few minutes Charity and I were back in that miraculous illusion of stability we call “reality” once again. I felt incredibly relieved… in the next few days, however, I learned that I wasn’t quite back in reality after all, or if I was, it was a new, hypercharged one. [In the nights that followed] I barely slept… I had two extremely vivid dreams in which I was pursued by a bearded man… a large mirror in the other room fell off the wall and loudly crashed facedown on the floor. It didn’t break. All night I dreamed that the bearded man was hitting me in the head with a pillow over and over again, laughing as he did it. I tried to hit him back, but my swings were feeble misses… the DPT trip had unleashed an angry poltergeist in my house. How could this be? I have never had a belief or even the slightest interest in poltergeists or the occult, but the signs couldn’t be more obvious. Suddenly I was in the midst of something for which I had no frame of reference, no preparation. What had I done? [My emph.]

I’m sure I’ll get in trouble for making generalizations about the Church again. If you don’t agree with the claim that mainstream religion reflects the materialism of the wider culture, help me understand: isn’t every heresy an attempt to re-enchant a symbolic interface, to re-negotiate a relationship with the animate hyperobject behind the symbolism? What was the Inquisition about? Why does the Church still try to suppress the emergence of new symbolic interfaces? (Side note: the statement cited in the article, from the president of the Vatican's Pontifical Council for Culture, that “religion is a celebration of life, and [Santa Muerte] is a celebration of death”… hoo boy. For a senior Vatican official, that is some spectacularly narrow thinking about the purpose of religion.)

I only just discovered The Emerald Podcast. (Thanks Milo and Adrienne!) This episode on syncretic gods is tremendous—all about how the hyperobjects behind these symbolic interfaces can sometimes choose to pack up and move, emerging in new places, in complete defiance of metaphysical conservatism, tradition, and cultural correctness. Totally worth the two-hour run time.

Please note that I am in no way endorsing the practice of driving Coachella attendees out into the desert as offerings to angry spirits. I never said that, and even if I did, you can’t prove it. And even if you could prove it—no jury in the world will convict me.

From this perspective, the tragedy of the whole “pretendian” phenomena is not that these people (who are often psychologically imbalanced) are committing fraud. The real horror is a person being so spiritually retarded that they can take modernity completely at face value: assuming that membership in a particular culture is just a matter of adopting its symbolic interfaces as aesthetic objects, while having absolutely no frame of reference for the deep systems of metaphysical relationality to which those interfaces belong. I wonder how “pretendians” might be treated if they were absolutely, unshakably committed to upholding the participatory consciousness rituals of the cultures they covet, dedicating their entire lives to those systems of relationality—rather than using a false identity as a tool for social and professional clout. (Maybe

can weigh in?)

Another great post, sir - and fun to see Andrew and Rebekah jamming with you here. This bit made me think of Tyson Yunkaporta saying that institutions want the products of Indigenous thought, but not the processes of Indigenous thinking:

"The bigger problem is not theft: it’s the ontological perspective telling us that the symbolic interface—the thing that can be stolen—is the primary source of value, rather than the relationship with the hyperobject it represents."

This is really helpful writing here, R.J.

They say we hate most the things in others that we struggle with in ourselves. Whatever so-called idol worshipers were doing in their own context, what the Faithful saw was a rigid, unmoving, immutable Thing pretending toward G-d. Just so with tradition stripped of the movement and breath that gave it birth, until it so stripped of mutations that it must try to lock its environment into stasis so that it can survive.

I like your chisel sharpening metaphor. Midrash is the grinding stone I think. Those under the spell of the literal-certain grieve the lost bits of metal filed off in the process because they only recognize the thing they are handling by its exact measurements. All change in form is loss I guess if you lose sight of the actual work at hand.

It interesting that Word can be all the components of your cosmos here: Mystery, Interface, and Enchanter (or according to the fairy tales Dis-enchanter).

Fascinating that Black Elk did his most innovative work blowing his breath into the lungs of the Sundance years after becoming a Catholic catechism. He sharpened the edge of its steel, reorienting the symbolic black away from a certain reveling in violence toward a grief over murder.

One time even G-d comes into Animal at Bethlehem (so they say) and all is innovation and new poetics, every existing interface is, at first , almost unrecognizable to all but those with ears to hear. All followers are instructed to do the same. What you bind/loose on earth will be bound/loosed in heaven. But Word soon becomes Text. Stasis offers a fixity of the species that can be comforting in a cosmos where a wolf can wade further and further out until, one day, its blow-hole is open to the starry sky and, hips empty, it wakes as whale.

Your point on poor design or bad form in innovation is well taken. More so considering the poverty we start from that is only mitigated like you say by the fact that it isn't a closed system. We may be helped past such because poor as we are, Someone might be looking for us right back. Still, hubris and a long history of the species "winging it" unto disaster does draw me toward a Keeping of sorts. Midrash is at its best when the shock of the innovation is brought to marrow by the ancestral familiarity of the conductor. Plus the well Dead. Like Stephen Jenkinson says, best to speak a language they might remember if you need their company, which I suspect we deeply do. And any game worth playing needs limit. Make a whale, but use this wolf to do it because no one should go mammaling in the sea without blood and bone, milk and lung. Even Shekinah started with the deep and Ein Sof the dirt when it came to making someone to interface with.

Just rattling on. Sorry. Good read.