(Un)mapping Phasmatopia, Part 3

Magic circles, terra incognita, and what we might find there.

I’ve had a couple false starts with this series. The habits of mind that go along with writing essays—particularly on Substack—aren’t well-suited to working with this topic. There is a tendency to follow the grooves of academic writing: describing abstract concepts, referencing other scholarship, building a web of language that is disconnected from the ground of the thing being described.

I began Part 1 with a description of an actual place in an attempt to circumvent that tendency. Part 2 got lost in the weeds a bit; the academic abstraction crept in, when I tried to describe how our cultural framing of haunted places takes us away from a true understanding of liminal spaces—how they fit into our world (or vice versa). I’m hoping this third installment will get us back on the trail, exploring an actual place and how we might (as the title suggests) find new ways of being in it.

I.

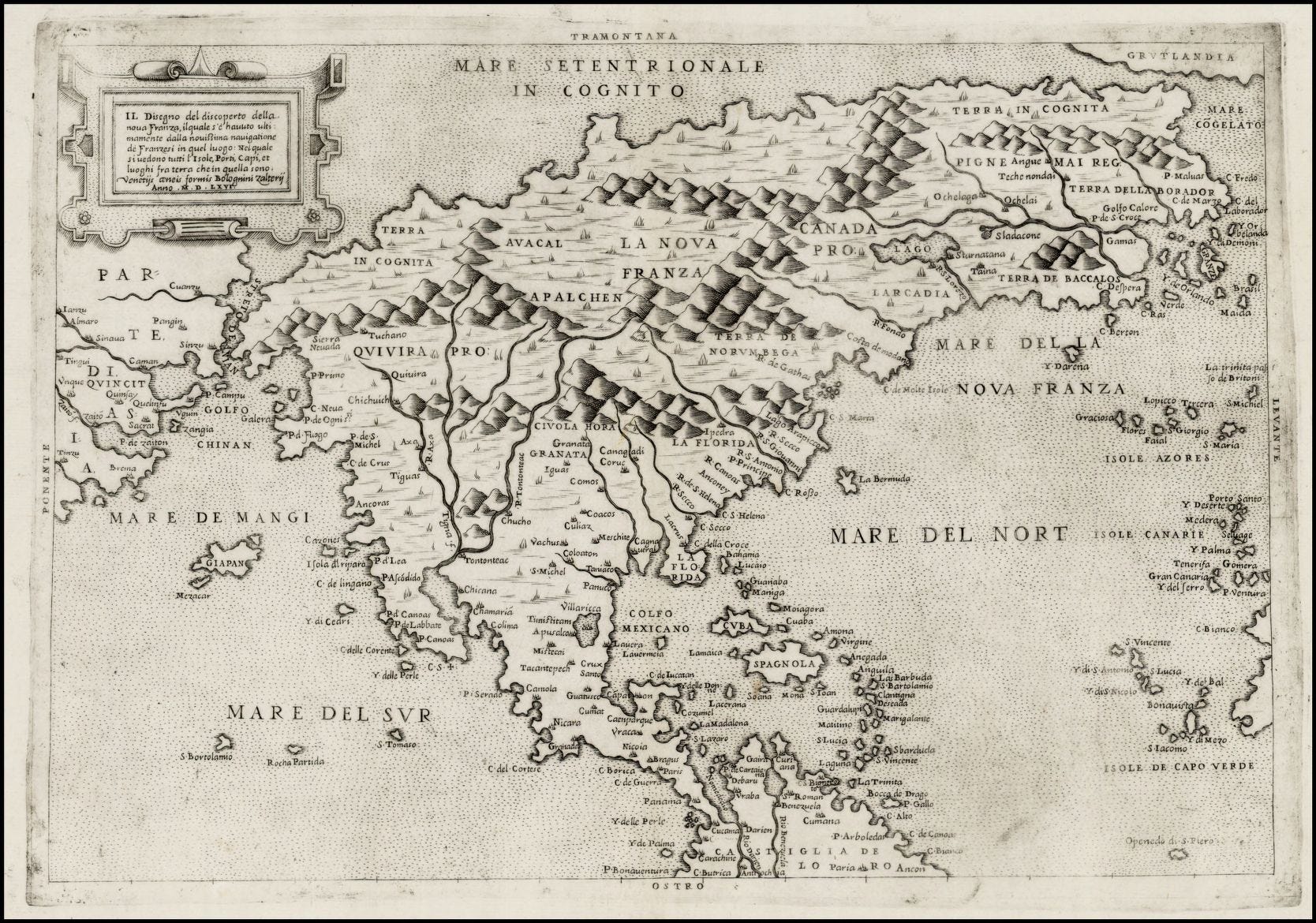

There’s something thrilling about looking at old maps like the one above.

We’re used to living in a world that is exhaustively defined. Every square inch of the planet has, by now, been photographed by satellites; teams of cartographers and surveyors have spent centuries identifying landmarks, drawing boundaries, naming rivers and lakes and mountains and forests. There is nothing left on the surface of the Earth that hasn’t been catalogued somewhere.

Only a few realms still frustrate our enthusiastic cartography: deep oceans, cave systems, and the outer reaches of interstellar space. And we’re busily working on ways to catalogue even those places. Our robotic emissaries can go where humans can’t. Every physical space in the cosmos can eventually—at least theoretically—be scanned and decanted into human understanding. Someday, in the far future, there will be no mysteries left.

This is ostensibly done to stock the storehouse of human knowledge. We’re told that this is for everyone’s benefit. Scientific data is universally valuable; with a bit of translation, and the proper training, anyone can make use of this knowledge. Everyone lives in the same reality, after all. This data describes how that shared reality functions, and if some data is good, more is even better.

However—behind this supposedly passive process of information gathering is a larger project of control.

Everywhere belongs to somebody now. These maps describe a jigsaw world of interlocking administration. The boundaries are drawn; the administrators are assigned; within those boundaries, the administrators determine what is possible—what is permitted to exist. In this official reality, there is nowhere on the planet that is unclaimed and ungoverned.

And again, this is ostensibly done for everyone’s benefit.

Lawless regions are bad for business. We mapped a world full of natural resources—land to live on, water to drink, food to eat, raw materials to harvest—and now somebody needs to determine how those resources are allocated. We invented the idea of human rights, and now somebody, somewhere, must be in charge of guaranteeing those rights for everybody on the planet.

These are all good things in principle. While we might debate the finer points of how these systems are administered, nobody enjoying their benefits would choose to completely unmake them. We imagine utopias in which the administration is perfected, and contrast them with dystopias, where the systems fail. But almost nobody would choose to restore the world to a state of total anarchy.

And even for those who would—it’s impossible.

Boundaries are set. Maps are drawn. Once the expectation of human control has been established—once that normative system of governance has been made real—it can’t be unmade.

The bargain for bringing the world under human control is a narrowing of reality. The administrators in charge of these systems define what is allowed to exist within their borders. By definition, they can’t allow the existence of anything they can’t control. This isn’t nefarious: it’s just the logic of borders. Once the boundaries exist, everything within them must have a place in officially-designated reality. Otherwise, the boundaries are no longer meaningful, and the administrators are out of a job. Special carve-outs can be permitted for alternative geographies—those described in fiction, folklore, and myth. But if they come into conflict with the official maps, those alternatives will be made unreal1.

That’s why it’s thrilling to look at those maps, with terra incognita boldly labelled: they’re artifacts from another world. They were drawn before official reality was made absolute, back when the administrators were forced to admit that they didn’t know what those places were—when those alternative realities were still unbounded.

II.

There is a strong tendency to think of the world shown in those maps as “how the world used to be.” But this is another illusion that modernity creates, contained in the very idea of a map.

Terra incognita is a blank space that must be filled in—an area of incomplete knowledge, awaiting “discovery.” This not only affects how we think about space, but also time. There was a past, when we knew less than we know now; there is our present (still imperfect) state of understanding; there is a future, in which we’ll know even more. The maps get more and more detailed, and the territory that humans control is described with greater fidelity. Those crude maps of terra incognita are pictures of the shadowed world of the past. Our high-resolution, multi-layered maps, with all the blank spaces filled in, are images of the present—always verging into the future, promising more detail, more data for the administrators to fine-tune their control over the environment.

In this understanding of time, we are always moving forward. Humans are always learning more; thanks to our mastery of technology, this knowledge is encoded in virtual storehouses that transcend the weakness of squishy human memory. Nothing is forgotten. We’ve banished terra incognita to the scrap-heap of history forever.

And this is all an illusion.

These maps are a hologram of persistent, perfectable knowledge. The map is not the territory. Maps are dead things, the skeletal remains of a memory. The actual landscape is always changing. As the world spirals along through cycles of becoming, remaking itself, the maps must continually be redrawn to keep up. If this mapping process falters—if there’s no one to collect or interpret the data, or if the landscape changes too quickly to be accurately surveyed—terra incognita unfolds itself again.

Those old maps aren’t pictures of how the world used to be and is no longer. They’re pictures of how the world really is, underneath all the layers of modeling and data, waiting to be uncovered. Terra incognita is always there. It’s paradoxically (from our perspective, at least) part of the past and also part of the future.

What we think of as the present, then, is an exceptional state that humans have created.

It’s a magic circle.

III.

Any delineation of reality is an enchantment2.

The ability to make a here and a there—to draw an imaginary line and make it real—is a uniquely human ability. An enchantment literally means “to speak something into being,” which is exactly what makes all the borders on those maps exist3. Casting a boundary means persuading everybody else that you control that space. The enchantment is a self-justifying phenomenon: it exists for as long as someone can make it real. Once that control falters, the spell is broken, the magic circle evaporates, and that segment of reality promptly reverts to its unbounded state.

A magic circle is a four-dimensional object. The operator who casts it is imposing her will on space and time: “Before and after the existence of this circle, this space remains undifferentiated, part of everything else; for as long as this circle exists—as long as I can make it real—my will is sovereign within it.”

Our official maps are a sustained exercise in drawing a magic circle that encompasses the entire material world. The enchantment behind it is as much metaphysical at is it geographical: with terra incognita banished, everything is subject to human understanding and, consequently, human control. As long as human authority within that circle holds, we can invent borders, draw maps, name everything under the sun, parcel out resources, and appoint administrators to manage all of it.

An implied monotheism is foundational to this enchantment. No matter what name we use for the architect of Creation—Yahweh, Jehovah, Allah, Science—there is only one absolute authority that governs the cosmos. We shine God’s light everywhere we go, and the maps we make are proof of our dominion. We invoke the authority of the Almighty in casting this circle; our divine mandate gives us the power to make it fixed and permanent. World without end, amen.

It’s a powerful spell. That magic circle has held together for a few centuries now. But we might not be able to sustain it forever.

IV.

My “Defining Utopia” exchange with Elle Griffin resolved into a familiar debate between optimism and pessimism: whether the world we build within that magic circle will be good or bad, whether the power we derive from its foundational enchantment will be used for good or evil.

And those are important questions—for as long as the enchantment holds.

The real question, for me, is whether our sovereignty is as absolute and permanent as we imagine.

How powerful is that magic circle? For how long will it last? What happens when the enchantment runs out, and the official maps stop corresponding with reality?

What will we find when terra incognita returns?

This is where the experience of people from outside modernity can be instructive.

Societies that we broadly refer to as “indigenous” or “traditional” tend to have a more complete understanding of their world-building enchantments. They know from learned experience that human sovereignty is fickle and fleeting. The enchantments that sustain them are the product of the combined orenda of the humans living within the world they build, constantly negotiating with the orenda of the more-than-human world. For them, the world outside the magic circle is the real world—the one that returns when human enchantments lose their power. Terra incognita is always there, surrounding the four-dimensional space that humans can see and control.

People who recognize the limits of their sovereignty have different ways of moving through the world. They don’t rely on drawn maps with demarcated boundaries: what good are those, when the world is always remaking itself, returning to terra incognita? Instead, their guides are songlines, myths, and poetry, living language that adapts to the living landscape around them. Relational tools, such as those modernity refers to as “animism,” “divination,” “astrology,” and “spellcasting,” are inseparable from these guidance systems: they’re wayfinding techniques for traveling through a world that can’t be captured in a two-dimensional frame. They’re what people use when the landscape around them is fundamentally unknowable, unmappable, and uncontrollable.

Again—these aren’t relics of the past. These aren’t primitive people holding on to how the world “used to be.” Terra incognita is never gone forever, and so the wayfinding tools for traveling through it are never obsolete.

The enchantments that created the modern world will end, eventually. This isn’t a question of optimism or pessimism: the sovereignty we exert over the material world is only as good as the magic circles we draw, and the maps we use to codify them. When the world shifts away from the borders we’ve set down—when the official maps no longer correspond to reality, when the data becomes irrelevant, when terra incognita creeps in around the edges and bleeds through the places that modernity has neglected—we’ll be living in another world, regardless of whether we think it’s good or bad.

And this is already always happening.

V.

The house I described in Part 1 is already part of this world.

If we followed the official maps to reach it, we’d expect to find a house like other houses: a neat little right-angled box for people to live in, with a number on the mailbox, one of many on an orderly street in an administrative zone with a name and a zip code.

That’s not what the house is, anymore.

This house is becoming something else—a synergy between human artifice and the living world around it. The story that was written in its walls will seep into the ground and become food for the fungii that trace its contours. It will no longer be a home for humans, but a place for other things that creep and hide. Calling it a bad place—seeing only what it once was, and never will be again—is an imposition of human values. It obscures what the house is becoming: a place for other lives to flourish.

Not just biological life, either.

There are exotic species of thoughts and feelings that can only be found in these unmade houses, abandoned roads, and haunted towns. The way we’re able to think in places like this is qualitatively different from our usual train of thought within modernity’s magic circle. Crumbling physical structures seem to encourage an unwinding of certainty. Without that certainty, we’re open to experiencing the whole landscape of the place: not only the physical environment, but also its emotional and psychospiritual formations.

And the folklore tells us that this wider landscape is populated by more than just our own imaginations.

If we keep reciting modernity’s invocation— “None of this is really real”—we can keep these alien ideas from manifesting completely, getting up and walking around in our minds. Modernity says that ghosts and other troublesome psychic echoes have no place in the present. Hallucinations are a kind of mental mutiny. Intrusive thoughts are a clinical problem. All these maladies can be dispelled with that same modern enchantment: none of this is really real.

But that enchantment starts to lose its power in these liminal places. The line between objective and subjective starts to blur when there’s no central authority to make pronouncements. Dreams mix with reveries. Time starts to slip.

Out here, sometimes, glowing lights appear in the sky. There’s probably a rational explanation for it. But who can you ask? There are no scientists, no priests. It might be a witch-light, or a lost soul, or a spaceship, or something even stranger. Maybe that particular light only appears once every ten million years; no human has ever seen it before, and no one ever will again. Who can say for sure?

If we stay out here long enough, under the grinning moon, we might decide that this place of uncertainty is more real than the narrow confines of modernity’s magic circle. This is derisively referred to as “going native,” or just going insane. But for all the supposed dangers of embracing that uncertainty, this eldritch landscape answers (sometimes literally) to some very deep human needs, beyond the basic biological functions allegedly championed by modernity. Terra incognita is our first and oldest home as a species. It’s the cradle of our consciousness.

We are told, and tell ourselves thereafter, that we don’t need to live in this wider world—that we have everything we need within the protection of the magic circle. But there’s good reason to doubt that.

Regardless of whether it’s true, the enchantments of modernity won’t last forever. We can only maintain the illusion of absolute control over the environment for a limited time. The process of updating the official maps is already faltering: even now, those maps point to towns that don’t exist, roads that can’t be ridden, and houses whose occupants are no longer human. As the environment becomes more unpredictable and harder to survey in the future—as the official maps become less accessible and less meaningful—many people will find themselves back in terra incognita. They might be surprised to find that some people have always lived there.

I’ve been referring to this place as terra incognita because that’s how it appears on the old maps. But that phrasing is insufficient: it’s a colonial term, referencing an irritating deficiency for the mapmakers—a bullseye for “exploration,” the imposition of certainty at gunpoint. When looking for alternatives (at least in the English language) we’re left with ontologically-bracketed terms like “spirit world,” “fairyland,” and unus mundus. Our language reflects the insistence that modernity’s magic circle encompasses all of reality, and not just a narrow slice of it.

In order to describe the commonality of perspectives from that wider world, across geographically diffuse cultures, throughout time—the myths, the folklore, the fiction—it helps to have a single term for everything outside the magic circle cast by modernity.

For my own convenience, I’ve been calling it phasmatopia.

This is why even ostensibly progressive cultures can’t resist bulldozing the occasional indigenous sacred space. “Sacred ground? That’s strange. According to our maps, there’s nothing here. Now kindly fuck off.”

This is easy to prove: look outside your window and try to see the state that you live in. Where do New York State or California exist? Nowhere, except the collective imagination of the people who have been told that those things are real. Somebody drew an imaginary line, and then conjured the whole machinery of administration and governance around it. That’s big magic.

I was arguing with you in my head about the term "terra incognita" right up to the last paragraphs. I knew you'd have to make that turn eventually!

I wonder if you aren't making too much of the difference between colonial mapping and indigenous mapping, putting the latter into the realm of myth or "spirit world," or your term, phasmatopia. To me, the main differences are that one is more permanent and the other ephemeral; and of course one served colonial purposes and the other mapped the home territory and that of neighbors. North American Indians, for instance, had very practical maps, but mostly relied on memory and drawing them in ephemeral ways. Here's an article I just found about the indigenous people north of you and me: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/cartography-in-canada-indigenous-mapmaking