I.

When I first started dipping my toes into applied metaphysics, I was struck by the sheer, staggering quantity of divination methods.

Astrology, of course, is most familiar to modern Westerners, followed closely by cartomancy. Then there’s osteomancy, geomancy, ornithomancy (i.e. fancy bird watching), bibliomancy—just to name a few that submit to easy classification. Aeromancy predicts more than just the weather. Pyromancy (outside of Dungeons & Dragons) represents a whole sub-class of methods involving fire. Beyond the classical systems are all the folk methods for augury: reading tea leaves, palmistry, looking for messages in cracked eggs and spilled entrails. The scrabbling and spattering of a beheaded chicken can tell you things, if you know what to look for.

In the end, there’s no way to create a complete taxonomy of divination. It’s a human institution. As a universal practice, it has as many forms and functions as there are different cultures in the world, different groups in different landscapes with access to different tools.

For some reason, early on, I was particularly struck by Malidoma Patrice Some’s description of the local cunningman in Of Water and the Spirit. His divinatory system shows a stark contrast with the aesthetic preoccupations of Western occultism. It was built around a collection of found objects and recycled scraps: odd-shaped rocks, bits of wood and rusted metal, maybe even an old can or two. Rude stuff, thoroughly unremarkable to the outside observer—but it spoke to him.

Materialists see this as pure chicanery. How can all these everyday objects be speaking a secret language? What invisible hand is shaping the fall of the cards—or the clouds, or or the tea leaves, or the cracks in burning bones—into an alphabet that these special people have miraculously deciphered? Aren’t they just making shit up? Can anyone credibly claim that these aren’t just bald-faced lies to fool the credulous for personal gain, money and influence and self-aggrandizement?

Admittedly, maybe they are, some of the time. But, crucially—not always.

More importantly, the material reductivism of “a cloud is just a cloud” and “cards are just cards” obscures a deeper human potential. It’s not that the objects themselves are behaving in an unusual way, necessarily. Instead, it’s the mind of the operator, using the physical interface as a catalyst for intuition.

II.

“But there’s nothing magical about [object]!” the skeptics wail1.

This is maybe half-true. At least insofar as there’s nothing actively magical about copper wire or quartz crystals, either. They don’t transmit music from the local classic rock station while sitting on a table by themselves.

And just like there isn’t a tiny Jimmy Page playing Stairway inside your radio, divination doesn’t rely on each physical object having a little homunculus living inside it2, devoted to translating messages into human language.

Mechanical metaphors are always the crudest, but on a very rudimentary level—the operator’s mind is an antenna. The divinatory medium functions as a tuning capacitor, which turns a broad spectrum of Divine Understanding into something scaled to human size. Intuition combined with imagination is the transducer that converts the signal into a coherent response.

Et voila. With the right components, you can build everything from a lake-sized radio observatory that can listen to the stars, or a Gilligan’s Island-style radio inside a coconut shell; the capabilities scale up, but the fundamental mechanisms are the same.

And, given the right atmospheric conditions—even the simplest setups can occasionally snag some strange signals out of the ether.

III.

This is why applied metaphysics will be eternally frustrated for scientific rationalists: it’s an inherently subjective process that only partially intersects with the physical world—obliquely, inconsistently, with apparently frustrating capriciousness.

For some people, the cards are just cards. For others, the cards are just cards some of the time, or even most of the time. But then, every once in a while, the symbols on the cards are etched with eldritch significance, the unmistakable witch-lights of transcendent awareness. And then the next day—or even in the next spread—they’re back to being regular cards again.

Successful clairvoyants have some combination of natural aptitude and developed skill in recognizing their own intuitive patterns. There’s more to be said about modern people’s atrophied intuition, after generations of treating rational analysis and monophasic consciousness as the only true measure of reality. But setting that aside for the time being—divination is, first and foremost, a vocabulary that corresponds with the intuition of the individual operator.

That means every divinatory query is a single-use cipher.

Mark this well: not every divinatory method, or every divinatory session, but every single invocation of Divine Understanding. Each time the cards are spread or the bones are tossed—that moment is its own singularity, never to be repeated, encoded in the flow of infinite possibility.

And there’s only one key for unlocking that singular code. It exists nowhere else but the seer’s mind, in all its amorphous, subjective complexity. The solution to the cipher is not something that can be duplicated or analyzed. It can’t be verified independently of one person’s perception at the moment of awareness, itself a cosmic singularity.

It’s not logical, least of all for the clairvoyant. The correct answer isn’t calculated. Like dowsing for water, or falling in love, the operator is led to a concealed truth by a subtle feeling of rightness.

So the physical media used in divination will always outpace the materialists’ attempts to catalogue them. It doesn’t matter if the external referent is eggs or entrails, clouds or crows: the real action is always happening deep within the mind of the seer.

IV.

This understanding of reality offers immense potential power to each individual clairvoyant. But it comes with its own system of checks and balances: that awesome potential can only be actualized one question at a time, one agonizing interpretation after another.

There is no guarantee that a single hit won’t lead to a long string of misses. If the operator overthinks the reading, finds it too complex to intuit correctly, it breaks. If the operator underthinks the message—takes too much for granted, puts too much faith in their special status as the Oracle—it breaks. God’s mercy on anyone who thinks they’ve found a Talking Skull to use as a reliable hotline to Eternal Truth.

The clairvoyant is perpetually stuck in a quantum state: having access to a cosmic awareness that transcends space and time, in potentia, while constantly having to worry if this is the moment the signal drops out, or if this is the moment their ego asserts itself and hijacks their reading, or if they really are just imagining it all.

It’s enough to drive someone insane, if they clutch divination too tightly as a skill that they possess, instead of an awareness passing through them.

This also introduces a layer of indeterminacy to every single prognostication as a verifiable truth. There’s no certain way to differentiate signal from noise for either the operator or the recipient. Just because the fortune-teller urges you not to get on the plane, and they sincerely believe their prediction—should you? What if they got it wrong this time? Now you have to trust your intuition about them trusting their intuition. Fuck.

V.

All this indeterminacy makes it impossible to tell a real clairvoyant from a charlatan, if such a distinction exists.

The uneven distribution of this potential means, on the one hand, a successful seer has a genuine opportunity to help people—and to help themselves get generously compensated for it. Every body has to make a living somehow. On the other hand, anyone relying on these abilities for a steady income will inevitably need to cheat.

You can’t force a miraculous reading just because the rent’s overdue and you need to impress an important client; in fact, that’s exactly the time you’re most likely to dial a dead line. But you can fall back on some cold reading, some lucky guessing, a bit of legerdemain. Just enough to keep some bread on the table until the Spirit comes back again.

Does that mean it’s all fake? Once again—if it’s an awareness passing through someone, and not a thing that they possess—can anyone tell a true prophet from a pretender, just by analyzing every single one of their past results? If a person’s record is anything less than 100% hits, and anything more than 100% misses, where’s the statistically significant threshold? And who’s to say the next reading won’t completely alter the math in either direction?

Whose insights are more trustworthy: the old Romani woman, reading cards since her hands were big enough to hold them, who relies on an aura of infallibility for her livelihood? Or the raving lunatic on the street corner—with no sensible agenda, no consistently coherent transmissions—who might very occasionally turn that complete lack of ego into an open channel for Divinity?

VI.

Although I’m afraid of wearing his name out—Gordon White is unavoidably a major inspiration for this publication, and I’ll be referencing him often.

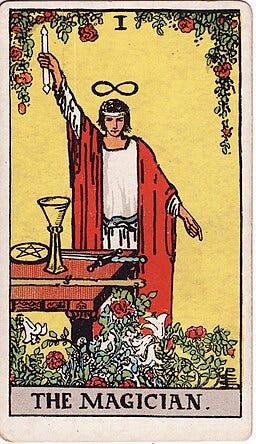

In his Tarot course for Rune Soup premium members, Gordon points out a fundamental shift in the portrayal of “The Magician” from the older Tarot de Marseille deck—pictured above—compared the newer Rider-Waite-Smith deck, shown here:

The card that became “The Magician” was originally known in the French decks as “Le Bateleur,” which means something closer to “The Mountebank,” “The Performer,” or “The Sharper.” As Gordon says, the figure portrayed in the Tarot de Marseille looks like he’s been run out of more than one town in the past. Le Bateleur is a dubious figure, on the fringes of respectability, not to be trusted. He might show you something amazing—or pick your pocket while you’re trying to keep your eye on the ball—depending on how the mood strikes him.

The later update transforms Le Bateleur into The Magician, standing proudly in his ceremonial robes, pointing confidently at knowledge both celestial and terrestrial, all encompassed within his understanding. Coming at it a bit high, maybe. This Magician is emphatically not a street performer. He’s a metaphysical scientist—an Alchemist—a card-carrying member of the Secret Order of Somethingorother.

This change in representation partly reflects the historical effort to make magic respectable (and profitable!) for European aristocrats in ceremonial lodges. But it also neatly illustrates the dual nature of magicians, clairvoyants, and anybody else attempting to channel these cosmic forces—both in how they’re seen by others, and how they see themselves.

Which is the real face of The Magician? What is the true character of someone who claims (and believes) they have the power to understand and influence the subtle weave of reality? Is it The Alchemist, or The Street Hustler?

There is no definitive answer. It always depends. On the person; on the day; on how the cards fall at any given moment, whether somebody is truly scrying the runes or just bullshitting their way through.

VII.

What’s really interesting is that the later portrayal of The Magician comes down hard on the side of magic as a methodical, literate, intellectual pursuit—a science—which can only be practiced by credentialed experts. This is supposedly what “real” magic is in the civilized world: an invisible appendage that responds to the will of the operator, governed by their mystical knowledge and metaphysical dexterity.

It’s an implicit rejection of the more shamanic, indigenous, phasmatopian experience of magic: something that occasionally just barges into your life and pole-axes you with visions, whether you’ve had all the right book-learnin’ or not3. It denies a world in which clairvoyants are more likely to be street preachers, lotus-eaters, and lightning-struck ramblers, rather than respectable scholars in bespoke robes.

Awfully convenient, for the people who want to sell books and charge membership fees for their Super-Duper Secret Societies.

VIII.

This is the simple truth that the profiteers will deny with their dying breath: clairvoyance is another form of athletic ability.

Some of it depends on baseline physiology. Some people are the psychic equivalent of Michael Phelps, the Human Dolphin—mutants who were just born different.

Some of it depends on access to resources. Being naturally gifted isn’t enough to make you an Olympic ski jumper if you live your whole life in the desert. Likewise, we can’t all be Delphic Oracles without some serious physical infrastructure and a major lifestyle change.

But you don’t need to be LeBron James to play basketball. You can just mess around on your own, working on your dribble and hooking layups. Eventually, you might decide to join some pickup games; with enough practice, you could easily be a respectable local player. There are plenty of people with deadly three-pointers who taught themselves how to play. Could you get dramatically better by paying for lessons and hiring a professional coach? Sure, if that’s the kind of game you want. Do you need to have a certificate for playing neighborhood hoops, or shooting baskets in your driveway? Absolutely not.

The same is true for divination. At the apex of the pyramid are the clairvoyant elite, who will very literally sell their souls to become human conduits; they treat blood sacrifices as table stakes, and don’t stoop to mingling with mortals. The broad base at the bottom is comprised of weekend warriors, doing the stuff that nearly anyone can with a modicum of focus—including the divinatory equivalent of a why-not miracle throw, drained into the basket from the half-court line. Everything in between is a mixed rank of gifted amateurs, semi-professionals, idiot savants, has-beens and could-have-beens; among them are the sharks and hustlers who misrepresent their abilities and claim to have knowledge not found anywhere else, which they’ll happily share with a chosen few, for the right price.

VIIII.

Once, in the funniest case of elder abuse I’ve experienced, I was booted from an occultist chat server—for arguing with some Gen Z kids about cartomancy.

They were deeply offended by the suggestion that anyone could use a regular pack of playing cards for divination, in place of the official approach to reading Tarot; worse yet—horror of horrors!—I proposed this as a good way for beginners to learn cartomancy, without laboring through the literature of the “correct” way.

Although we didn’t have time to discuss all the details before I was hurled out politely asked to move on, I got the distinct impression that these junior True Initiates had spent a very long time memorizing card correspondences and fixed-position layouts. They were probably throwing Rider-Waite cards, and wearing out the covers on their Little White Books—which is all fine. That’s certainly one way to do it. I’m sure it works well for many people. Lord knows I’m no expert (although there was that one time, which only goes to prove my point).

What I took exception to, in the tone and tenor of the conversation’s terminal stages, was the suggestion that my way was somehow inferior—that because I hadn’t spent years sweating over the mathematical precision of meanings and learning whole array of spreads, I was somehow doing it wrong.

Again—I didn’t get a chance to ask for clarification. Whatever was truly in their hearts that day is lost to history. Nevertheless, it sounded very much like a bunch of people getting indignant at the suggestion that their own sunk costs might not have been valuable long-term investments, trying to cover it up with a desperate appeal to authority.

Which is a shame, for three reasons:

This is how occult pyramid schemes get started.

As described above—when it comes to divination, the power does not (apologies for banging this same drum again) come from some fealty to metaphysical conservatism, an imaginary authenticity from back in the mystical time when Real Magic Happened. The Celtic Cross spread was not invented by Merlin himself. Instead, the juice should come from the operator’s ability to trust and interpret their own intuition, which functions independently of any particular system.

Playing cards are a thoroughly effective way to do Tarot-style readings, if you’re not a complete muppet. (More on this below.)

X.

Some systems of divination have been refined over hundreds or thousands of years. Those that rise to the top have revealed the right blend of objectivity and subjectivity: not presenting so much granular randomness as to be completely illegible, while also not so fixed in form that they resist intuitive interpretation.

For example, the letters of the Roman alphabet are too constrained—too self-referential—to be useful for divination, without some determined reverse-engineering. “A” means “A.” It stands for a certain set of vowel sounds; combined with the other letters, it forms one phonetic building block for words that carry a more comprehensive meaning. On its own, an “A” is literally just an “A.”

In a pinch, you could make up your own associations for each letter. For example: “A” is for “Adam,” the first named person in the Abrahamic mythos. Then you add the idea of fatherhood, the patriarchal line, masculine creativity. “A” is also for “apple”; now you’re introducing elements of… what? The Promethean gift of knowledge in the primordial Garden, maybe. The fundamental incompatibility of human ego with the more-than-human world. The sudden dual awareness of vulnerability and responsibility as an adult, a potential husband and father. You can riff on this for as long as you like, and choose whichever poetic associations speak to you most evocatively; then build the letter “A” into a container for all of them.

Repeat the same process for the other twenty-five letters, and presto: you’ve got your own homebrewed system of divination. Toss your Scrabble tiles down on the kitchen floor and start prognosticating. Dazzle your friends; horrify your local priest.

While technically possible, this example illustrates the fundamental premise: there is no inherent significance in the letter “A” that makes it a divinatory tool. It only serves as a placeholder for the subjective interpretations that you, the operator, have chosen to load into it. And when it shows up in a reading, there will be an additional layer of subjectivity, with your intuition determining which of the symbol’s multiple associations “make sense” in a particular context. What rises to the surface will turn on one specific question, in one specific moment, in combination with an infinitude of other atmospheric variables.

Doing it this way is also a hell of a lot of legwork.

Compare the Roman alphabet to Hebrew letters, with their built-in symbolic and numerological associations; every word is a combination of pre-established ideas, each with its own poetic logic. Same again with our incomplete reconstructions of the Elder Futhark, or the Celtic ogham. The symbolic density of the I Ching is derived from an “alphabet” of sixty-four hexagrams, and each has its own distinct character. In these, we can see that written language was originally, very literally, a form of magic—that almost every symbol was understood to be a living thoughtform, metabolizing a complex of meanings and associations as it evolved. Even in the Roman alphabet, the letter “A” grew out of something that was once a Bull4; only much later was it stripped down to a simple phonetic signifier.

(Whether it’s a coincidence that the Language of Empire is built on the skeletal remains of these disenchanted thoughtforms—the reader is left to decide for themselves.)

So there is some value in learning the intricacies of a pre-existing symbol set. Historical and cultural significance add more depth and resonance to an individual’s personal associations with the symbols. Taking the time to learn the traditional forms and meanings of something like the Tarot or the I Ching will provide a more nuanced symbolic vocabulary in a shorter amount of time, in place of a solitary effort to re-invent the wheel.

But anybody who tries to tell you that there’s only One Right Way to use these tools—that you can’t trust your own intuition—is full of shit. They’re either trying to dazzle you with their own arcane knowledge, or sell you an expensive book, or both. Pay no mind.

XI.

For modern Westerners, playing cards make an easy symbolic interface for learning divination.

The familiar Bicycle deck is built on the chassis of the old Tarot, so it’s already a short hop away from cartomancy. And it’s familiar enough that you don’t need to learn a whole new cultural vocabulary in order to interpret it. At the same time, it’s not so open-ended that you have to start from scratch with your own associations, like in the alphabet example above.

Here are the basics that I use:

The simplest spread is a three- or five-card tirage en ligne (“drawn in line”), also known as fortune-telling style: cards laid down in a row from left to right. Left is the beginning of the narrative, or the ignition of energy; right is the end of the story, or the exhaustion of energy.

For yes/no questions: a flush of all Reds is a hard yes, whereas turning up all Blacks is a hard no; a mix of Reds and Blacks is a soft yes or no, depending on the balance of colors. Unlike flipping a coin (too much binary randomness, not enough intuitive grist) the disposition of the different suits will tell you something about the why of the answer.

The suits represent types of energy:

Hearts are Cups in the Tarot system. Water element. Warm energy. Fluid. Emotional health. Social, artistic, domestic. Romance and family; generative power. Positive associations are emotional; accommodating; balancing; affectionate; healing; nurturing; restorative. Negative associations are mercurial; distracted; equivocating; hysterical; peevish; maudlin; indulgent, or just plain drunk.

Clubs are Wands. Earth element. Cool energy. Organic. Physical health. Craftwork, business, and legal matters. Career and integrity; persuasive power. Positive associations are industrious; studious; adaptable; practical; respectable; disciplined; loyal; diligent; cultivating. Negative associations are isolated; preoccupied; overburdened; stolid; bookish; arrogant; domineering.

Diamonds are Pentacles. Fire element. Hot energy. Molten. Spiritual health. Commerce, finance, civic politics. Money and reputation; provocative power. Positive associations are brilliant; inventive; charismatic; innovative; dynamic; passionate. Negative associations are reckless; impulsive; hot-headed; venal; materialistic; extravagant.

Spades are Swords. Air element. Cold energy. Frozen. Psychological health. Governance, (para)military and underworld activity. Shadow work and demons; compulsive power. Positive associations are intelligent; ambitious; cunning; calculating; strategic; determined; resourceful. Negative associations are cerebral; cold-blooded; merciless; venomous; vengeful.

Numbers for each suit represent degrees of intensity, starting with Aces (first, lowest) up to Tens (ultimate, highest). Odd numbers are unstable, unresolved energy; even numbers are stable, resolved energy. Eventually, you can get into numerological associations (e.g. One of Cups is a solitary drink, while Ten of Cups is a party); for the basic reading, just look at chronological fluctuations of intensity throughout the spread (e.g. from left to right: high to low, low to high, chaotic vs. ordered, big vs. small differentials, etc.)

Court cards are active human subjects. Some traditions get very literal, always reading these as real, living humans: Kings are older men; Queens are older women; Jacks (or Pages) are young men or women. If this feels too constraining, you can treat them as actors in a play. The important thing is to keep the logic of the reading internally consistent: within each spread, the court cards are either real people or imaginary actors, not a mix of the two. However, that doesn’t prevent you from switching modes between spreads, as long as you don’t cheat your intuition or confuse yourself.

Each court figure represents or embodies a particular type of energy. The King of Swords is a Macbeth figure. The Queen of Swords is Cersei Lannister. The Jack of Swords is Feyd-Rautha. King of Hearts is the Big Lebowski; Queen of Hearts, Marge Simpson; Jack of Hearts, the Manic Pixie Dreamboat of your choice. And so on. These examples might be a bit too on the nose, but you get the gist.

This is all more or less conversant with the Minor Arcana of the Tarot deck. There’s some added complexity in the Waite-style “picture” decks, which have symbolic elements illustrated on all the cards. But the Minors of the so-called “pip” decks, like the Tarot de Marseille, have the same structure as playing cards (with the addition of Knights as an extra courtly class).

What playing cards lack, for better or worse, is the Big Powers represented in the Major Arcana. These are sometimes understood as agents of Fate: demigods, superhuman entities, or otherwise implacable forces (hyperobjects?) that shape events beyond human control. In a more stripped-down version of fortunetelling style, the figures of the Major Arcana are just an additional cast of neutral characters taking the stage. For example, the Hermit isn’t necessarily some powerful mythic figure; he could just be a guy with a lantern. Is he lost? Is he looking for something? It depends on the question, and what the other figures in the spread are doing. Regardless—the lack of the Major Arcana will either limit your readings or simplify them, depending on your appetite for a whole different level of correspondences beyond the Minors.

This is just a starting point. Here’s a YouTube playlist explaining a similar system for reading playing cards. Notice the difference in correspondences. Neither this approach nor the one above is the Only Right Way. There are enough free resources available online to get you started without spending a fortune; some of them are listed below. Treat these all as inspiration. Once you get going, you will invariably find correspondences that speak more persuasively to you. But this basic structure serves as a framework for development:

One pocket dimension represented by the full deck.

Two polarized fields of energy, representing a fundamental duality between two halves of the deck.

Four diversified forms of energy between the two polarities, represented by the suits.

Four groups of actors within each suit, personifying or embodying each of the energetic forms, represented by the court cards.

Ten levels of incremental intensity within each of the energetic forms, represented by the pip cards.

In a full Tarot deck—the addition of a group of unaffiliated agents, represented by the Major Arcana.

One stage across which the dramatized answer will unfold.

Most importantly, remember: what you’re doing is not reading the cards in an analytical way, but learning to trust your own intuition, which is not something that can be taught.

Happy hunting.

Additional resources:

The Cartomancy Episode of What Magic Is This? along with its very generous show notes.

The Tarot Course for Rune Soup Premium Members.

The extremely prolific Camelia Elias is a cartomancy powerhouse and a champion of intuitive divination; she offers a whole slew of free essays at Read Like the Devil, and a galaxy of podcast interviews on a wide range of cartomancy topics.

Weird Studies has an intermittent series of episodes on the Major Arcana, going deep on one card per episode.

For my money, the most frustrating example of reductive materialism is the supposed debunking of Ouija boards. Every once in a while, some midwit will pop up and act like they’re pulling off an amazing intellectual coup by pointing out that a Ouija board is a mass-produced piece of cardboard, and—get this—the planchette isn’t actually moving by itself. It’s just the ideomotor effect, dummy! Checkmate, occultists. Of course, as is so often the case, that innocent “just” is an ontological stalking horse. The whole explanation is begging the question: what part of the subconscious mind is driving the ideomotor effect, exactly? How can we be sure that “our” subconscious isn’t being influenced from something outside our minds—that there’s even an “outside” or an “inside” to begin with? What if the motive power behind the effect is not the board or the planchette itself (duh) but the semi-conscious invocation of opening our minds to something alien, turning our neurological system into an open channel? This is why scientific testing for this stuff is pointless: if you treat the Ouija board as “just” plastic and cardboard, that’s what it will be. If your test subject is too self-conscious to be in a truly receptive state, because they’re aware they’re being tested—you’re not accurately reproducing the right conditions. And as always: maybe it just doesn’t work if the Others think you’re an asshole.

For animists—in a cosmos with Mind as the substrate for reality—every physical object represents a psychic extrusion with its own potential for inspiration, its own form of memory. This means that ritual objects (Tarot decks, runestones, yarrow stalks, bones, etc.) are servitors that organically develop their own personalities through sustained interaction. This can also be done through deliberate enchantment, like the Trithemian method of drawing spirits into objects.

If you’re looking for something properly magical to watch or read, Jonathon Strange and Mr. Norrell is a tremendous book (turned into a BBC limited series) that does a phenomenal job of dramatizing the conflict between “respectable” magic—scientific, scholarly, practical, structured—and the older, earthier, more chaotic stuff. The character of Norrell is explicitly gatekeeping “real” magic: buying up all the magical books and using the mundane legal system to regulate access, which he thinks will prevent anyone from discovering it on their own. Meanwhile, Strange is an intuitive magician, a self-taught amateur who stumbles into a more shamanic method. This puts him at odds with Norrell’s ideas of propriety—even though Norrell is secretly trafficking with eldritch powers beyond the control of his “respectable” magic. There’s some unfortunate racism against faeries; otherwise, it’s extraordinarily good stuff.

Maybe the Old Bull?

Looks like Gordon noticed the same thing I did, though I came to a different conclusion. Here's my entry for The Magician:

The Magician is usually shown holding a wand in one raised hand. He is often standing next to or behind a table filled with magical symbols, with the sign of infinity above his head.

Imagine what happens when you watch actors on a stage, or when, as a child, you played “make-believe.” Something strange occurs: things that don’t actually exist become real in those moments. It’s as if there’s another realm of meaning we forget about in normal life, but we can enter it — at least for a little while — when we play.

Play is an important idea to keep in mind when you see The Magician. In some of the oldest surviving Tarots, he was named Le Bateleur, which was an acrobat or carnival performer. Through their acting, they showed people wonders and what else might be possible.

Think on the double meaning of the verb, “act.” What do the performers in a play do? Well, they act. But when we do something, we also act.

That’s why this card is associated with communication, agency, imagination, and especially with manifestation. The Magician holds a wand towards the sky, but his other hand points firmly to the ground. An idea is just an idea until we ground it into reality. And the more we create, the more open we become to new ideas and to inspiration.

When you see The Magician, ask what you need to act upon, what you need to make real in the world. Nothing ever happens if we live only in our heads, and even the smallest actions change things. While The Fool seems to leave the future to chance, The Magician knows we have a say, too.

It’s probably time you started something you’ve been putting off, and you need to begin somewhere. Don’t be afraid of your influence or power. Don’t worry that you don’t know or aren’t enough yet — you’re only at the beginning, anyway. Go find out what else life can be, and do it with curiosity, playfulness, and wonder.

Hey R.G.! Loved this piece. You have a knack for writing about these things.

"Like dowsing for water, or falling in love, the operator is led to a concealed truth by a subtle feeling of rightness."

I'm always looking for the everyday examples, the "commonplaces" in the sense that JMG describes the topoi in old-school rhetorical training (https://www.ecosophia.net/the-truths-we-have-in-common/): the thing you can point to that is an experience familiar to people for whom the framework you're coming from will be unfamiliar or alien.

Like Gustavo Esteva telling me, "If you want to talk about the commons now, especially in Europe, especially in cities, then start with friendship." It took a couple of years of chewing on that to grasp that friendship is one place where we still have a common understanding that the world is not made of resources: if someone I thought of as a friend treats me as a resource, I say "I feel used", and everyone knows what I mean. From here, it's possible to break through into the old distinction between commons and resources, rather than the modern distortion (or approximation, at best) that describes "commons" as a way of managing resources.

So, going back to your "subtle feeling of rightness", I've found myself drawn to Suely Rolnik's description of "the vital compass", which came to me from Vanessa Andreotti. This seems like a promising commonplace: we all have the experience of certain settings or people in whose company we feel ourselves coming alive, and other settings or people around whom we feel something inside us quietly dying. Probably most of us were not taught to attend to these feelings or put much weight on them, but they seem to be still available, an animal awareness of "rightness" or "wrongness" that lives in the guts.

Reading your piece, I saw more clearly the connection between this kind of cultivation of trustworthy subjective awareness, which I'm reflecting on in preparation for the autumn series, and the more explicitly occult intuition which you are offering a frame for.

On a different note – I'm currently reading Carlos Eire's They Flew (because Amitav Ghosh told me to!) and, early on, he writes about the Reformation as the cut-off point where miracles were suddenly treated as something that had been possible in Biblical times but were no longer possible. This took me back to your thread about metaphysical conservatism and my sense that the monotheisms are less monolithic in this respect than they often present themselves as being, that what we're looking at is a historically layered locking down of the metaphysical, and that – like most conservatisms – metaphysical conservatism is a more recent phenomenon and less reliable representation of how things have been in the past than it claims to be.