Back in October, the introductory post for my book project laid out some pretty big metaphysical claims.

It might have sounded like I was saying that all movies are prophetic—or, maybe, that all zombie movies are in some way prophetic.

So I want to nail down the difference: what exactly, if anything, separates an ordinary piece of zombie-themed entertainment from something as portentous as George Romero’s original Night of the Living Dead?

Teasing that apart will mainly be the work of the book. But we can also look at a case study—a movie that draws from the same source material as Romero’s work, technically within the same genre, without (in my opinion) rising to the level of something truly prophetic.

The Dead Don’t Die, Jim Jarmusch’s 2019 film, is just such a case.

This essay series will explore what happens when a derivative piece of art tries to climb beyond its reach. Please keep in mind that I’ll be trying very hard to avoid the typical film-review thing: dunking on the director out of meanness, or showing off what a super-smart Enjoyer of Serious Films I am. Looking critically at these things is extremely important, beyond just the usual sport of cultural jousting and product-review culture.

Modern culture would have us believe that movies are a technological update of a primal human tradition—blockbuster-sized campfire stories, freed from the limitations of human imagination, brought to life on the big screen. This is obviously a boon for filmmakers who want to invoke a quasi-spiritual heritage for an otherwise sordid industry.1 But it’s fundamentally wrong in two important ways.

First, it diminishes the power of true storytelling: in elder cultures, stories aren’t like magic; stories are magic, full stop.

Second—this false equivalence overstates the cultural value of movies. It insists that we’ve gained more than we’ve lost. They had stories; we have stories—except their stories were just boring old words and gestures. Our stories are brought to you in Dolby Digital Surround Sound with 8k resolution and the latest CGI technology. So now, not only can you watch a guy pretend to be Beowulf, you can actually see inside his pores, to a really frightening degree, and hear him breathing as if he was standing next to you on a crowded train. Progress!

We shouldn’t accept this trade at face value.

Instead, we should look carefully at the baubles held up as our own modern “myths,” to spot the forgeries and find the things that are missing.

The (Literal) Magic of Storytelling

This gets us into the metaphysical weeds pretty quickly, so bear with me.

Storytelling is a form of enchantment that literally wraps another world around the audience.

Pay close attention to this phrasing.

The conventional formulation is that stories transport audiences to another world. Modern people, accustomed to “the world” as a material thing, are tempted to read this as an analogy. Moving from one world to another—if such a thing is even considered possible—is understood as a question of spatial distance. Stories don’t have to power to move physical bodies; therefore, to say that “stories transport audiences to another world” must be figurative.

“Sure, I know what that’s like,” people will say. “I’ve felt totally immersed in a really good movie before.” But this confuses a powerful aesthetic experience with something genuinely transcendent.

For people living in a fundamentally different cosmology than our own, there is no meaningful distinction between a story and an enchantment.

True myths, truly delivered, are a portal into sacral time: the Otherworld, the eternal Everywhen in which the ground of being is continually renewed. Correctly recalling a myth—in person, with the correct mindset, in an evocative setting—means leaving one world, the mundane world, and traveling into another. This breaks down the modern distinction between active performers and a passive audience. When participants do this deliberately, they bring themselves and the story-world together.

The story-world is a storehouse for truth. Whenever people get caught up in their own affairs, they can return to the place where the truth is kept, to regain the proper perspective. New people can be brought into the story-world to receive their own measure of truth; they bring it back with them into the everyday world, as productive members of a shared culture.

These living stories keep people in right relation with the cosmos. The story-world transcends the progression of history—linear time, as experienced by humans—because its truths prefigure our world. They aren’t facts derived from the world, in the way that reductive materialism would have us believe;2 these are the truths that shape material reality, the way a melody shapes sound into music.

In scientific terms, myths are elemental events in a kind of quantum superposition: from our perspective, they have both already happened and never stopped happening. In the same way that a melody can repeat itself throughout the course of a song—can even change in pitch, rhythm, and contour, while still remaining essentially the same as it was in “the beginning”3—these are eternal truths with varied expressions, as seen at ground level in the human realm.

Within mythic time, the Creators have some general ideas about how they want the ordering of things to be. But they haven’t fully made up their Mind. It’s only ever the second moment after Creation. Spilled blood, steaming still; present world made from a god-slain dragon, and all our lives floating in the vapor of it.

Myths, translated into narratives at human scale, recall those unresolved truths from the first victorious moment after primeval chaos was/is subdued.

Everything else is just details.

Big Stories, Little Stories, Bear Stories

In properly mythic cultures, there are something like Big Stories and Little Stories, just as there are Big Dreams and Little Dreams.

Little Stories are told primarily for entertainment: fables, campfire tales, legends, local lore. Nevertheless, they are still (again, literally) a form of magic.

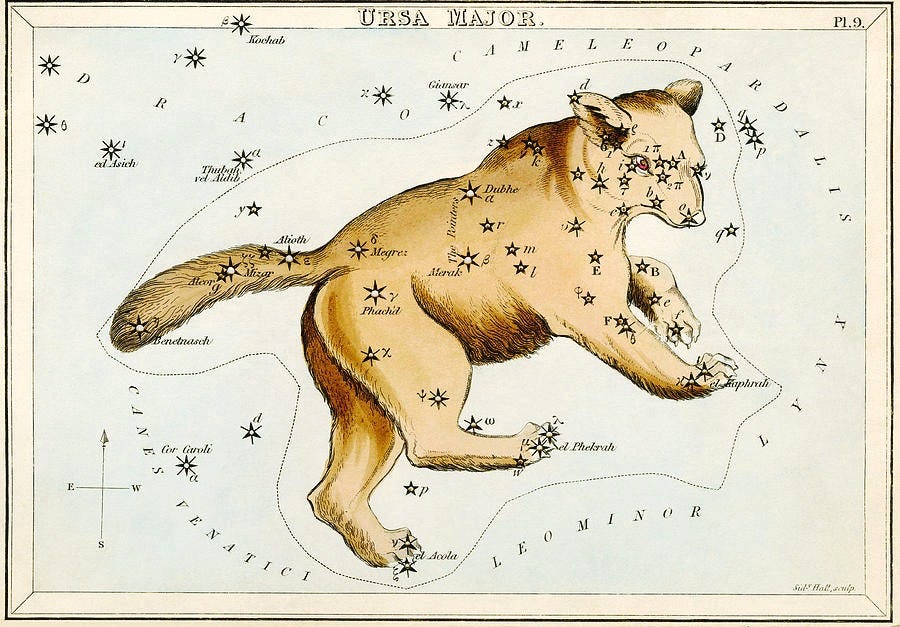

For example—telling children the story of how Bear lost his tail (a bedtime standby in our home) brings them partway into a world of mythic resonance. This is not a Big Story that recalls the foundations of the cosmos. It’s a child-sized story that serves as a useful diversion while subtly introducing kids to the workings of something larger. The enchantment of the story takes them out of a reality in which there are many individual bears, and into a world where there is one Bear—the eternal source of bear-ness, the personification of all bears.

Because we don’t share a language with bears in our world, they can seem like furry automatons. The science-world in which children are educated encourages this perspective. But in the story-world, Bear is a person; rather than describing bears as the biological product of mechanistic evolution, the enchantment recalls the genesis of bear-ness in human terms. In this world, Bear’s essential qualities—and, by extension, the bear-ness of all bears—is a result of his4 choices, and the consequences of those choices.

These stories represent a greater truth about the world: not a scientific truth, but a mythic truth. The amusing details are incidental. What matters is the personhood of the characters involved, the way they relate to one another, and the implication that the material world is somehow shaped by those interactions.

Big Stories are grown-up versions of the same enchantment. They are more sophisticated, in the sense that they deal with bigger concepts and darker possibilities. But they’re still reminding people of the same kinds of truth: this is how the world really is. This is how the world always is, underneath all the bustle and clamor of human life.

Modern filmmakers claim to be doing the same thing. But if this is the standard for mythic storytelling—in spite of its pretenses, in spite of the trillions of dollars poured into the entertainment industry, employing some of the greatest creative talents in this world—modern cinema is missing the mark. It manufactures very few products that rise even to the level of Little Stories, and almost none that could be considered Big Stories.

The truths told by movies (if any) are, usually, already part of the mundane world. There is no real need for transmutation. Modern, secular culture has no sacral time. There are no mythic truths that need to be continually revisited.

Nowadays, even overtly religious movies are only reciting from the old brochures, putting on pantomimes of historical events in the material world, falling far short of transporting an audience into the Otherworld they supposedly recognize.

If this was the trade we accepted when we gave up traditional storytelling for mass media, then we have lost something substantial as a civilization.

Dumb Movies and Broken Myths

Modern movies are immersive entertainment spectacles. They are materialist fantasies, showing us the world as we (or somebody) wants it to be, without necessarily offering a way to realize those dreams off the screen. Although we can roughly divide them into two classes— “dumb” movies and “smart” movies—they are serving the same essential function in different ways.

Dumb movies are unashamed of pandering to the vulgar aesthetic preferences of an audience. They are purely transactional, and honest about it. Dumb movies are hook-ups. They promise nothing more than a rush of excitement, an adrenaline kick, a dopamine dump. Big lights. Loud noises. The voyeuristic opportunity to watch pretty people do interesting things. The contract between the creator and the audience ends when the screen goes dark. They get some money; you get to fill a few hours, and leave with a bit of cinematic afterglow. Job done.

Smart movies aspire to higher principles. They are still materialist fantasies, but of a different kind. The world they imagine is more than just toned bodies and fast cars, big guns and stacks of cash. Smart movies want the real world to be better than what it is. They are didactic productions, implicitly or explicitly trying to teach us something about how the world works. Presumably, we can take this knowledge and do something with it—make the world a kinder, gentler, happier place, either more or less like the one shown on the screen. It’s the audience’s responsibility to take the proffered inspiration and turn it into real-world action.

This is touted as the superior cultural value of “good” cinema and smart movies, compared to dumb movies and lowbrow entertainment: smart movies make us want to be better people.

In a perverse way, the movie industry is trying to re-create the conditions of true mythic time. Smart-movie creators want modern cinema to be the Dreaming of this world. Just as those ancient seekers gathered around their campfires to recall the melody of Creation, modern audiences are meant to enter the Eleusinian grottos of the movie theater to receive their measure of truth. We should go to the movies to recall What Really Matters—to let that knowledge shape our conduct in the real world.

The mundane world is always changing; the heroic figures captured in the memory of this cinematic Otherworld are ageless and eternal. When we forget how the world should be, we can always go back into that shadowed temple and watch Indiana Jones punch some Nazis, just as he always has, and always will.5

Unfortunately, this system only produces broken myths, because the creators misunderstand how true myths work.

Filmmakers fall victim to the same epistemic blindness that plagues the rest of modernity. They imagine that we, as humans, decide what will be revealed to us. Nothing can resist our explorations forever. With the right amount of effort, anything real can be simulated under artificial conditions. It’s a simple matter of willpower.

Myths, from this flawed perspective, are just stories. Artificial objects. An artful way of transmitting information from one brain to another.

This ignores the fact that myths are living things, and—like so much of the real world—when they are pinned down to materiality, cut apart and turned into slices of celluloid, they become something different.

They die.

Very few modern filmmakers have a proper respect for true myths. And so, while are phenomenally capable of rendering dystopias and utopias in immersive detail, they seem to lack the proper language for what is actually happening—how this world is unfolding, and potentially ending.

Smart movies are drawn to the intersection of hyperobjects with the human world: elemental forces like Love, War, Genius, Promethean Ambition, Nature, Gravity, Death, all colliding with human society, as something more than an excuse for a car chase or a fist fight.

This should be the proper domain of mythic storytelling. But because modern creators are compelled to describe these forces in strictly materialist terms, they’re writing with their hands tied.

In our world, filmmakers can’t tell a story about climate change as the wrath of gods whose covenants have been broken. They can’t tell a story about the development of the atomic bomb as the totem of an eldritch, cosmic darkness, funneled down from a mythic dimension (even if Oppenheimer himself was able to see the connection). Can’t talk about artificial intelligence as a demonic entity.

And even if they did, the ontological bracketing of “fiction” and entertainment would imply that these things were only true in the movie-world, not in our own.

To bridge that gap would require some truly mythic storytelling, and an ontological leap that most creators aren’t prepared to make.

Sometimes, though—things bleed through.

Stay tuned.

To be continued in Part 2.

Among other things, a money laundering racket for sexual predators, which also occasionally serves as a propaganda wing for the U.S. military.

Modernity’s whole concept of natural laws is a head-trip in itself. Briefly: in Western epistemology, a law is information in the form of an object—a factual imperative that functions independently of any subjective interpretation. Modern science would answer this question affirmatively: “If a law falls in the cosmos and nobody hears it, does it still make a sound?” Presumably, the entire universe could be erased in some sort of anti-material cataclysm, and the facts would still be left dangling in the void, waiting for new life to re-evolve and discover them again. Reductive materialism leaves us with the impression of “natural laws” as something like empty clothes left hanging in a cosmic closet. It’s much more interesting to push that basic logic further: if these truths are Out There, somewhere, whether or not there are individual minds to apprehend them—doesn’t that suggest something like a Big Mind as the firmament of reality? Something like (and I hate reducing organic phenomenon to technological analogies, but it’s useful here) the hard drive on a multiverse-sized computer? And couldn’t the information on that hard drive—the memories of the cosmos—start to cohere into ideas, like simple lines of code? Which might become more complicated codes, with their own memories, simpler and self-contained versions of the Big Mind. Like computer programs. Or gods.

Does a song ever really “begin,” in an absolute sense? The melody already exists as a whole, somewhere. Only when it’s pulled down into linear time does it appear to have a beginning, a middle, and an end, which then repeats itself until the musician gets tired of playing it. But the melody itself was always-never-not-there, woven into the tapestry of possibility that is Music Itself. Music is a hyperobject. Or a god(dess).

I’m sure there are other stories that address Bear’s feminine qualities, in which Bear is a “she.” This particular story recounts Bear’s masculine behavior, and so Bear is a “he.”

Lemme tell you: as far as mythic axioms for modernity, you can’t do much better (or chillingly worse, depending on your perspective) than “It belongs in a museum!”

Great piece, R.G. Have you read DBH's All Things Are Full of Gods? If not, I think you'll enjoy it.

Really love this and your particular inquiry here. The Dead Don’t Die was in fact a bit of a head scratcher for me, other than seeing it as an artist saying “enough with all the Zombie garbage, it’s over used, please stop. I hope this kills the genre.”

Then a couple years later we have a zombie series’s on HBO where the zombies come from a fungal outbreak and the entire story is based on a video game. I couldn’t help but think this series was the logical end of the mushroom as metaphor. The number of essays talking about our collective mycelial networks and connections are everywhere, from Dark Mountain to Sophie Strand and of course stemming recently from Paul Stamets “Mycilium Running” all the way back to the 60s counter culture finding the Shaman Maria Sabina.

The weird irony is that I could cut here and not mention the elephant in the cultural room which is the dumb film Avatar. I remember when I first watched it, it was technologically a marvel but the dialogue felt pathetic, though the story was undeniably a mythic story. I watched it fairly recently and somehow the timing and pacing seemed kind of perfect, it was somehow less dumb, especially in comparison to something more recent things like The Mandolorian. If we look at the time line of when Avatar was released and all that is implicit in this “dumb” myth so much of what is being written about is about the same ideas embedded in so much ecological/environmental writing today, yet it is almost never acknowledged as source material. Avatar functions similarly to the Matrix, it implicitly shows that we are not our bodies. Also we humans tend to not think of ourselves as animals, but we are animals. Animals do not see themselves separate from nature (animism.) Everything in nature is connected, our ancestors literally return to and become part of nature and can be directly accessed through mother trees which could be seen as the mycelial networks connected to trees.

It’s also a degrowth story and warns that by seeing ourselves as separate from nature man will destroy the sacred, and further distance himself from seeing his/her own connection to it. Lastly it clearly offers a contrast between indigenous/pagan values and those of secular materialists.

Look at the timeline of when Avatar was released 2009 (to be fair Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Gathering Moss was in 2003, Mycelium Running 2005) and then look at when Dark Mountain was started. I don’t mean to diminish the work of Dark Mountain in any way, I love it and find incredibly thoughful writing as well as community there. But how many of the essays and ideas in Dark Mountain were being implicitly discussed and displayed in a dumb film that made over a billion dollars at the box office? Even if you hate Avatar it created a universal framework for understanding these ideas that were largely isolated and trapped in books geared toward middle class educated “liberals.” Avatar as a dumb film with a central protagonist as a soldier managed to escape the political divide that tends to befall most written environmental work.

As this is getting long I’ll just add one major spoke worth considering to your argument. “They aren’t facts derived from the world, in the way that reductive materialism would have us believe;²these are the truths that shape material reality, the way a melody shapes sound into music.”

This seems like a clear argument, but if John Cage were here he would likely vehemently disagree with this as wrong or an over simplification at best. Cage was an avid forager, studied Hinduism, Buddhism etc. music for him changed over time from using melody to turn noise into music into something that could be a designed process, randomness with prepared piano, and on to something like a Buddhist practice of presence. 4’33” is about hearing what is happening all around you at any given time, it’s about taking the reigns off our desire to construct and orchestrate music and realize we are already in music all the time 4’33” as a concept it inherently makes music Animistic if we simply go to the wood and listen to our own 4’33”.

Again trying m to keep this brief I’ll just say I don’t disagree with your path of inquiry, I just think it’s missing a pillar and that is a real understand of Art and how Art functions. Film has the capacity to tell myth, but also to show art, and transport us. Like Cage, David Lynch was also into transcendal meditation and openly said he was just a channel for the ideas, though he was specifically interested in image, the ideas came from outside himself. I’m not sure he wanted to change culture, I’m not sure if he had a strong interested in mythology (personally doubt it.) I do think he wanted to step aside and let the fertile unconscious speak through images and in doing so was more interested in Art. Myth tends to lead us in a particular direction (order) and is perhaps more akin to a parable. Most effective Art presents something unknown, a field of uncertainty, that the mind does not understand. It often has no referent or purpose other than to create an experience of mystery. The meaning, purpose, connections to this unknown are all individual and may be accepted and built upon or rejected and pushed against (creative chaos and destructive chaos). I am of course oversimplify things. Art can be linear and ordered and have specific aims and goals. Myth can be used to undo an ordered understanding and create a field of chaos. We can be transported to filmic time/world or we can be in perfect presence and also somehow through presence escape our material selves.

There are plenty of bullet holes in this as I’ve written it quickly off the top of my head but as you are writing a book thought I’d share and hope this is helpful, rather than me just being a performative dick hole.