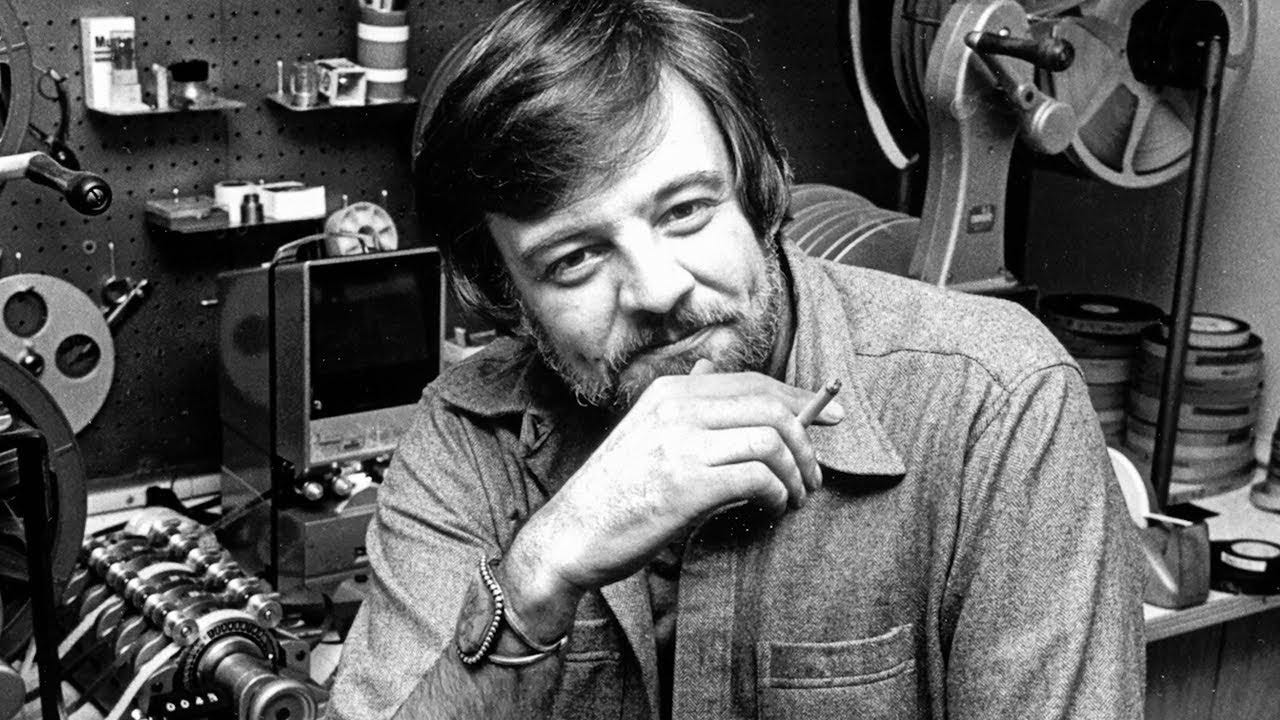

George Romero, Genius

"I thought it was some sort of punishment, something happening that was beyond our understanding."

I’ll be presenting “Prophecy of the Living Dead: Zombies, Prophetic Horror, and Cinematic Necromancy” over at Weirdosphere on Saturday, November 1, at 8PM EST, which will include a discussion of Night of the Living Dead. Registration makes you a member of Weirdosphere and gives you access to all their outstanding programming and content. Come and see.

When it comes to explaining how a cultural product like Night of the Living Dead gets made, from a materialist perspective, there is a boilerplate explanation of “the creative process.”

These are generally accepted truisms: art is made by artists; artists invent the things they make; some artists are geniuses; a genius is just like a regular artist, but better.

Scientists have yet to figure out which part of the brain contains the wiring for the “genius” lightbulb, presumably left disconnected in ordinary people.

We’re all familiar with the heroic character of the genius. The lone visionary. The imaginative alchemist. Someone who sees hidden treasure in the ordinary stuff that other folks walk past every day.

Our history is a litany of geniuses. We learn their stories along with the alphabet and simple sums. It’s important to understand their biographies, because creativity (so we’re told) is a mechanical process. The formative years in the life of a genius are composed of providential moments, which fill the mind with a mysterious substance called “inspiration.” This gradually accumulates, like snow building into an avalanche. Under the right environmental conditions, the potential energy of inspiration is released as the kinetic energy of “creativity.” This, supposedly, describes how art is made.

These narratives always start with the creator.

In the case of Night of the Living Dead, it starts with George Romero.

Look:

Here’s little George Romero—George Junior, named for his father—in 1953, only thirteen years old, at his family’s apartment in the Bronx, playing with a borrowed 8mm video camera.

One of the first moments of inspiration, settling into his mind.

Here he is, shooting footage for his first science fiction movie, The Man From the Meteor, which will get him arrested for dropping a flaming dummy off the roof of a building.

In his spare time, he rides the subway back and forth, using his allowance money to rent a film projector. He carries it home—along with the precious, clattering reels of other people’s stories—excited to set up his own screenings in the living room.

If we (the omniscient audience) could catch a glimpse of his face, gazing out the through the spraypainted glass of the train’s window, we might see the beginnings of a mischievous glint in young George’s eyes: the daydream of his own name up on the theater marquee. Maybe he could actually do this.

More moments, piling up.

Here’s George in 1959, working on the set of North by Northwest, unimpressed by the bald, jowly director’s studied manner and lack of panache: “I could do better.”

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. College days. Working as a bicycle courier, delivering newsreels: picking up the developed prints from the film lab’s editing room—glue pots, scissors, cigarettes, sack lunches—peddling back to the broadcasting station, sprockets whirring, flying past the gate, twenty-four frames per second.

Getting hooked on the go-go-go energy of moving pictures: cut it, print it, fix it, roll it.

The twinkle in his eye growing brighter, like the light shining in a darkened projector room.

Finally getting behind the camera, shooting commercials to pay the bills, with just enough money left over for a sixer of Iron City at the end of the day. Then a real gig, filming some far-out kids’s show, talking puppets, jeezus, what was it again, Mister Somebody’s Neighborhood? A trippy scene, but with final cut privileges, the chance to craft his own vision for the first time.

The audience chuckles at these little winks of fate, nodding along. It’s all so obvious when you roll the tape back: each moment building to a dramatic reveal, running forward in orderly succession, already predetermined, but creating the illusion of spontaneous motion.

Somewhere in the background of all this, George writes a novella: horror, monsters, darkness, the dead. He calls it “Night of Anubis”—

Boring. Cut that. Guy sitting in a room by himself, clacking away on his typewriter? A narrative vacuum. It sucks. Get rid of it. This is a story about lights, camera, action, the genius in the director’s chair. Keep rolling.

The weight of destiny, piling up.

Finally, we get to the good part.

Pittsburgh, 1967. The Summer of Love and unbearable heat. Riot-sparked smoke in American cities. Jungles burning in Vietnam. Jim Morrison’s voice on the radio: “Come-on-baby light my fi-yer.”

George and his friends having lunch, bitching about the film industry, low pay for grunt work, no creative control, and have you seen the crap these other hacks are selling to theaters?

“We could do better.”

Something begins to shake loose.

George slaps the table in a fit of bravado: “We’re gonna make a movie!”

All those piled-up moments of inspiration reach the moment of critical mass. They begin their stately slide into George’s consciousness, like a train pulling away from the station: the one brilliant idea that will change everything.

A mad rush. Lights! Camera! Film stock, Christ, we’ll need to buy our own film, you have any idea how much that stuff costs? Math, money, mayhem. Actors! What about a script? Who’s gonna direct this thing?

From here, the audience understands that making art is a process of manual labor. The rest can be shown as a montage:

George Romero, soon-to-be-famous director, explaining his vision to the newly-instated board of Image Ten Productions.

Shaking hands with investors.

Mustering cast and crew.

Peering through the lens at an unremarkable rural cemetery.

Laughing maniacally, splattering his moonlighting actors with buckets of chocolate syrup—looks like blood in black and white!—and goading them into taking ravenous bites from fake arms and legs.

Shouting about the unfinished script, the unchosen name: “Monster Flick? Night of Anubis? Night of the Flesh Eaters? C’mon, for fuck’s sake!”

At long last, the now-infamous title card appears: Night of the Living Dead.

Audiences across the state, the country, the world, shrieking at the ghoulish cannibals brought to undeath on the big screen.

George Romero’s name in lights on the marquee out front.

The world changed forever.

Flash forward forty years: the lumbering independent filmmaker is now a gray eminence, stooped with age, wired up to yet another microphone.

He is a cinematic institution.

“Godfather of the Dead,” they call him.

Smiling, he waits patiently for yet another round of the expected questions.

That’s what happens when the schlocky little B-movie you made for fun with your buddies accidentally redefines an entire genre of storytelling.

Nobody’s interested in what the precocious teenager from the old neighborhood was trying to envision, all those years ago. When his first movie came out, people marveled at how he did so much with so little; in the years since, critics have watched his movies and asked how he managed to do so little with so much.

The rotten bastards.

Now, whenever he’s up on stage, people only want him to play the hits.

Who cares about Martin, or The Crazies, or Bruiser?

Tell us again about the Living Dead, George: that’s the story we want to hear.

He’s famous for creating the monsters that took over the world—and yet he’s become their creature, at least as much as they are his.

This is probably how the guys in Skynyrd felt about “Free Bird.”

Isn’t it amazing, his interviewers say. The son of a working-class family of immigrants, completely transforming the landscape of horror.

In a few short years, inspiring legions of imitators across the world, in every country with even the bare bones of a film industry.

Teenagers with borrowed cameras now copy his ideas.

The monsters he invented have crawled off the movie screen; they shamble through video games, TV shows, books, cartoons, and the imaginations of children barely old enough to talk. In fact—they’ve become such unremarkable stock characters that audiences are bored with the relentless onslaught of half-decayed, bloodthirsty, reanimated corpses.

How does he explain it?

George has been playing this role a long time, and knows exactly how to hit his mark. The chuckle, the sly grin, the humble modesty of a man with nothing left to prove: “Aw, jeez, I mean… anybody coulda done it. I just got lucky.”

All those little moments of inspiration, piling up silently in his mind: just luck, really.

(Did he ever get that avalanche rush again, after the first time?)

(Did he spend the rest of his life chasing that same high, never to catch it again?)

Now: here it comes.

He can feel it.

Like an old boxer reading the subtle cues on his opponent’s face—the slight change in stance, the shoulder’s involuntary twitch, telegraphing the punch before it’s thrown—he knows when the question is coming.

He’s been asked thousands of times, in hundreds of places, by people wanting to steal a little bit of magic for themselves:

Where do you get your ideas from?

Ah, Jesus.

He’s too old for this shit.

Maybe now, finally—maybe now is the time to confess, like the good Catholic his mother raised him to be.

He’s lived with this charade long enough.

The genius. The big man in the director’s chair. The guy with the brilliant idea.

The kid from the Bronx whose mind was cracked open just that much more than everyone else’s, scooping up all those moments of inspiration before they drifted to the ground—saving them from being trampled, storing them up for the right chance.

Where does he get his ideas from?

He could say it out loud, this time.

Blow the lid off. Reclaim some of the rebellious energy that launched his career. Go out with a bang.

It would be so easy:

“‘Where did the ideas come from?’

“I have no fucking clue.

“Not only that—I don’t know if we should even call them ‘ideas.’ Thomas Edison had an idea for the lightbulb, right? It didn’t come crawling at him out of the dark, grabbing at him. He didn’t wake up in a cold sweat with the feeling of hands still clutching at him.

“That short story I wrote back in the ‘60s? ‘Night of Anubis’? I didn’t write that on a spring day in the park, just for kicks. I wrote it because I had to get those things outta my head, to pin them down, somehow, in the real world. Christ. Felt more like an exorcism than a story.

“I mean… you know who Anubis is, right? Egyptian god of the Dead? Jackal-headed guy, guards the boundary between our world and the Underworld? He brings the dead over to the other side, watches over them—and makes sure they don’t come back. He’s in charge of all the rituals to help the dead find their way over there. So they don’t wander back over here. So they’re happy.

“Now, you know who’s not Egyptian? George fuckin’ Romero. And for the life of me, as I sit here today, I can’t put my finger on why I chose that name for the story, or why I thought about using it for the movie. I mean, christ—none of those yinzers in Pittsburgh even knew who Anubis was.

“Why not call the movie Judgment Day? Or The End Times? or Holy Fuck, Saint John Was Right? Why Anubis, for chrissake?

“The studio thought we should have something in the script to explain why these dead people were coming back to life. So we had all this stuff about viruses and aliens, right? The thing about the space probe, the radiation, whatever—that made it into the final cut.

“But I never bought it.

“I always felt like, from the beginning, this whole thing was happening for a bigger reason. If the dead were crawling out of their graves, it was because we’d screwed up. We must have owed some kind of debt. And they were coming to collect. I thought it was some sort of punishment, something happening that was beyond our understanding.

“Sometimes I feel like I can picture Anubis, standing in that blood-red river up to his ankles, trying to direct all these dead people over to the other side. Like a traffic cop in Midtown, at rush hour, you know?

“And they’re not listening to him. Just not hearing him.

“They’re all blind, deaf, and dumb down there. Nobody’s read to them from the Book of the Dead. They don’t know where they’re going, or how to get there.

“So they’re turning around and coming back here, to the world they know.

“And Anubis is just standing there, right? Shrugging his shoulders, like, whaddya want from me? I tried to tell you how to help these people. And you didn’t listen. They’re your problem now.

“I can see all this, sometimes, and it feels like somebody should warn people. Somebody should let everyone know. Because I’m not sure it’s only happening in the story.

“I’m not sure where the line is, between the story and the real world, because in my head, there is no line. It’s all happening in the same place.

“Maybe that’s just how it really is.

“Does that answer your question?”

It would be so easy, to finally get this off his chest.

But then, of course, all hell would break loose.

Poor George. We always wondered when he would finally crack up. He used to be so brilliant. Such a genius. All that blood and death must have gotten to him in the end.

George, we’re confused: whose idea is this, exactly? Whose name goes on the checks we’re supposed to write? Should we make this out to you? Or to the Egyptian god of the Dead? Seems like Anubis should get a cut of the action. Union rules, you know. Har har har.

He wouldn’t only be risking his own legacy as a filmmaker: it would be an indictment of the entire creative industry—an entire way of life—Western civilization as we know it.

The world wanted people to enjoy its products untroubled. The customer is always right.

And George Romero, the famous-but-potentially-unemployable director, was a regrettable human component in an industrial process. People couldn’t seem to live without their fairy stories, and so he was tolerated. As long as he obeyed the system’s logic. Fulfilled his purpose. Served his function.

To suggest his little horror story might actually mean something, might somehow be real—that would be a serious breach of contract. It would upset the customers; this, in turn, would upset the investors. They would shout at him, like Ned Beatty shouting at Peter Finch in Network:

You have meddled with the primal forces of nature, Mr. Romero, and we won’t have it!

When the tiny microphone is finally unclipped from the broad expanse of his once-fashionable lapel, he can hardly remember which of the approved answers he gave in response: “Other people’s films, novels, current events, poetry, folktales, journaling, my own life. Blah, blah, blah. It’s all inspiration. That’s where the ideas come from.”

Maybe it doesn’t matter.

His time is almost up.

It won’t be long before he reaches the distant banks of that river himself, and meets the jackal-headed god who guards the crossing.

Maybe he’ll have a chance to explain, when his heart is taken out by Anubis, placed on a set of golden scales, and balanced against the weight of a feather:

“I am George, son of Anne. I did my best to warn people about what’s happening, when the dead can’t get across. I did what I could. The only way I knew how.

“I tried, anyway.”

Maybe that will be enough to earn him safe passage to the other side.

And then we fade to black.

George's final resting place and Tombstone was about a 5 minute walk from where I used to live in Toronto at the city Necropolis.

Would always ALWAYS tip my cap as I went by.