There’s a simple question at the heart of the book I’m working on: from an animist point of view, how bizarre and unsettling is it that we’ve accepted zombies—vengeful, reanimated corpses—as stock characters in our culture?

Why are some representations of the Reanimated Dead in our media seen as cultural tropes, mechanical plot devices, or empty signifiers for something else? And why do other portrayals seem to be the Dead themselves—giving a collective voice to what dead humans might express to the Living in the present world, if they could communicate with us?

It’s a significant question, now that zombies have become almost universally recognized cultural objects. Zombies are everywhere, somehow. They’re featured in video games, TV shows, and movies for adults—but also in cartoon form, in products explicitly aimed at children. The phenomenon has reached such a level of cultural saturation that my three-year-old knows what zombies are, solely through the power of memetic osmosis, without ever being deliberately1 shown a piece of zombie-centric media.

The ur-text for contemporary zombies is George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968). While Romero wasn’t the first to use zombies or revenants as narrative devices, Night marks the origin of the contemporary “living dead” zombie. The creatures in Romero’s movie have a few important characteristics: first, they’re reanimated corpses with diminished intelligence and a degraded physical form; second, they’re part of a global phenomenon, which simultaneously emerges in multiple locations; third, they’re capable of self-replicating through some form of biological or supernatural contagion. These features make them distinct from other revenants in folklore, like vampires, and also from their precursors in the “voodoo zombie” horror genre.

Most highbrow critical examinations of horror movies try to decode what zombies “actually” signify2 . In these analyses—particularly of Romero’s canonical films—zombies are stand-ins for conservative white racism, or middle-class cultural repression, or First World consumerism. They represent the violence of the Vietnam War, or the horror of political assassinations; the rage of oppressed minorities, or godless scientific development. George Romero encouraged these comparisons himself, when he was interviewed about his work. Critics ran with the idea, and so the artistic cognoscenti almost compulsively interpret zombies as metaphors for something else.

But the cultural power of the Zombie Apocalypse has transcended these critiques. Romero’s zombies permanently altered global culture. Night of the Living Dead spawned a legion of international imitators within a few decades of its release. Less than sixty years later, we can hardly imagine a world in which the walking dead are only familiar to B-movie fans and midnight cinema audiences.

As we’ve moved further away from the original canon, zombies have evolved into a new breed of monster in the classical sense: a part-human, part-animal hybrid. A strictly materialist view would say that these monster-zombies are a useful narrative device for creators who want something identifiably human-shaped for the heroes to blast apart with no moral complications. The zombies in the old voodoo horror movies were sympathetic figures who needed to be rescued; the new breed are irredeemable, and exist purely to be destroyed.

Significantly, neither one of these cultural tropes—zombies-as-metaphors or zombies-as-monsters—retain a literal sense of what they originally were, and still explicitly represent: dead human bodies, brought back to physical life.

Without the accumulated layers of cultural and academic distancing, it seems incredible that something as elemental and inherently visceral as the Dead should be so thoroughly objectified and trivialized.

This begs the question: what is it about zombies that makes this distancing possible?

Even on a purely psychological level—what is it about modern culture that makes us so comfortable with this desecration of “the dead,” who we no longer see as our dead?

It’s partly a function of scale. The global emergence of the zombies in Romero’s story is what originally made them so compelling. Previously, zombies and other revenants were seen as localized threats. Ghosts, ghouls, vampires, and voodoo zombies could be isolated and destroyed. They were often the undead servants of an individual villain: the curse could be stopped by defeating the creator-vampire or necromancer, restoring whatever taboo had been violated. In these cases, the revenants retain their personhood; the audience is encouraged to identify with them, at least insofar as viewers transpose their horror onto the zombies’ diabolical creator.

Night of the Living Dead turned zombies into a purely destructive force. There was no wild-eyed sorcerer to defeat; no spell to break, no antidote to offer. The element of contagion made the walking dead into a self-perpetuating scourge. Individual zombies weren’t deliberately created as part of some devious scheme. All sense of personhood and relationality was stripped away. Unlike the older model of crude servitors, these were unstoppable, unnatural animals—murderous flesh-robots stuck on autopilot.

In the face of this threat, individual people and small groups could fight their way to temporary safety through sheer dumb luck. But once the plague got rolling, anyone could do the math: it was only a matter of time before humanity was wiped out. These new zombies threatened to overtake much more than a single plantation on a Caribbean island. They could doom the entire world.

If there is anything stubbornly metaphorical about zombies, it’s as avatars of catastrophic global mortality—the existential horror of the Atomic Age.

Prior to 1945, people imagined the end of the world as a mythic Armageddon: an eschatological termination, a gesture of Divine Will. Total human extinction was only discussed in theological terms. We had memories of cataclysmic floods and devastating plagues, but there had always been survivors; post-disaster populations always bounced back.

The earthshaking debut of nuclear war brought the realization that humans could be the authors of their own total destruction. We discovered that we could easily obliterate our entire species ourselves, through avarice and sheer stupidity. And suddenly—nowhere, nowhere, nowhere was safe.

The Zombie Apocalypse made this specter of global annihilation even more horrifying. Zombies literally represent humanity turned against itself—a plodding recursion of soulless, mindless violence. Romero’s vision wasn’t a Biblical Flood or a cleansing celestial fire. There was no Heavenly Host; no final confrontation between Good and Evil; no comfort in the ultimate revelation of God’s Plan. An atomic blast had a kind of sun-scorching majesty, at the very least. But even the Wagnerian Götterdämmerung of a nuclear holocaust was withheld. Instead, zombies brought only the relentless, grubby, senseless push of preventable slaughter. Desperate feet scrabbling in darkness. Truncated screams of the dying. One helpless life after another, brought to a gurgling end, rising again, until nothing human remains.

Seeing this, critics instinctively attempted to rationalize zombies. They were just too much on their own terms: too libidinal, too merciless, too damning. So they were turned into more digestible metaphors. They came to symbolize the human vices that we could control—or at the very least, persistent social ills for which we could accept responsibility.

The old voodoo zombies conjured the colonial horror of rebellious slaves and pagan cosmologies. The new breed of zombies were still symbols of barbarism, but in a different way: not the fear of a disrupted colonial regime, but a failure of democratic liberalism. Ventriloquized by cosmopolitan commentators, these monsters confront upstanding citizens with the consequences of senseless violence spreading unchecked. Voodoo zombies were defeated by a simple triumph of rationalism in a closed society; the Zombie Apocalypse was the nightmare of a new globalized politics, in which order could be undermined everywhere at once. Supposedly, the Living Dead are imploring us to choose sensible international discourse over hatred, greed, and xenophobia.

But this should lead to deeper questions: what if the Dead presented in these visions are more than just sock puppets in a modern fable? What if the creative process that produces them is part of something much weirder than modernity permits?

Most importantly—what if the Dead are allowed to speak for themselves?

An outstanding cinematic counterexample to the zombie phenomenon is presented in Dreams (1990) by Akira Kurosawa.

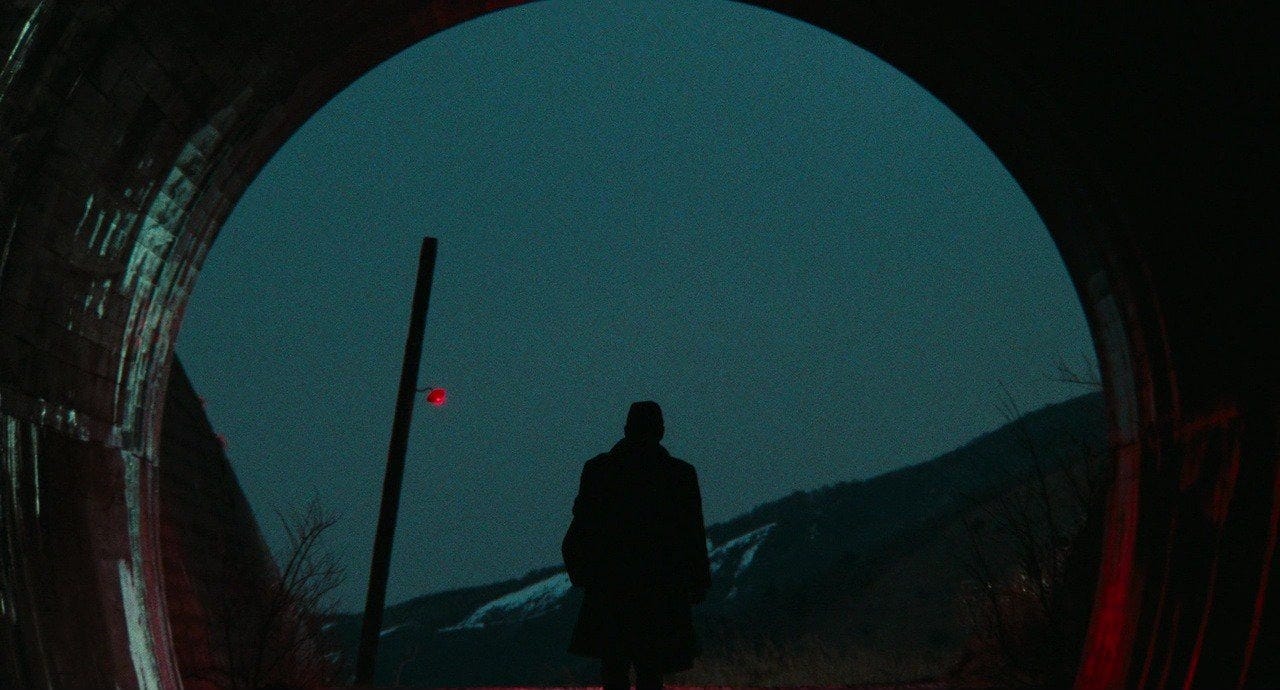

The film is an anthology of vignettes taken from Kurosawa’s own dreams, one of which is “The Tunnel”3

The revenants in “The Tunnel” share some clear similarities with Romero’s zombies. They’re not portrayed as ethereal ghosts; within the context of the film, they feel solid, like walking corpses. Although they’re (literally) more disciplined than Romero’s shambling hordes, the massed group of bodies—ragged clothes, vacant faces—recalls the ghouls from those earlier movies. Even the stark concrete of the derelict industrial setting seems more suited to a modern splatterfest in Romero’s Rust Belt, while the quasi-Gothic themes of “The Tunnel” could just as easily be dramatized on a misty battlefield.

In fact, the scene shares so much visual language with the zombie genre that a first-time viewer, conditioned by Romero’s influence, might expect the undead soldiers to rush their living counterpart and tear him to pieces.

Despite these similarities—there’s no temptation to see the Dead in “The Tunnel” as any kind of metaphor. They’re unambiguous in their presentation: these are the Dead, full stop.

The obvious answer to why Kurosawa’s revenants are so evidently literal is that they’re humanized by the narrative. They’ve been brought back to confront the Living, represented by the Lieutenant, their former commander. They condemn their treatment in life, and in the afterlife; they compel those left alive to grapple with their own mortality.

Unlike Romero’s monosyllabic monsters, these Dead can explain in human terms what they want. They’re caught in a spiritual dilemma. Movingly described by the resurrected Private Noguchi, the soldiers of the doomed Third Platoon are partially unstuck from time: still clinging to life, even though they’re dead. In accordance with a well-known metaphysical principle—practically universal in supernatural folklore—it’s implied that these soldiers were killed so suddenly and violently that they were left unable to recognize their own deaths4.

Private Noguchi can’t believe he’s dead. He remembers being in his parents’ house, alive, as if he was just there. The Lieutenant tells Noguchi that this is a fragment of his final semiconscious moments: badly wounded, bleeding out, Noguchi revived long enough to describe his dream, before dying in the Lieutenant’s arms.

Even after Noguchi is convinced of his fate, he still imagines that his parents are in his childhood home—just over there, he says, pointing to a light on a distant hillside. He’s sure they’re waiting for him to come back. Except, from the Lieutenant’s perspective, his parents already learned of their son’s death; they’ve long since given up waiting. It’s not even clear if the distant light is actually Noguchi’s home, or just an illusion of desperate hope.

This is the limbo state of displaced future-past that traps Noguchi and the rest of the Third Platoon. They can only escape through the intercession of the Living, in the person of the Lieutenant. So the revenants assemble for one final muster.

Again, Western audiences might be relieved when the undead soldiers don’t immediately attack their still-living commander. But this relief is fleeting. The Lieutenant’s role in the tragedy (at least in the English-translated dialogue) is ambiguous. He confesses to “sending [the soldiers] out to die”; it’s unclear if this was a personal act of betrayal, or the irrevocable consequence of orders received and carried out on the battlefield. He describes “staying behind” while the rest of the platoon was killed. Was this cowardice? Or simply the machinations of fate beyond his control?

The undead soldiers wait, standing impassively at attention, while the Lieutenant pleads his case. The uncertain audience waits too. Violent revenge against the Living still seems likely.

There’s a deliberate dynamic of relationality here. The Dead need the Living; the Living need the Dead. The soldiers of the Third Platoon are asking their commander to recognize their deaths, to release them from the limbo of uncertainty. The Lieutenant needs a chance to atone for his guilt, to reckon with the burden of being left alive—having his own death forestalled, while so many others were killed.

The ritualistic nature of the encounter is heightened by the formal procedures of a military review. Across the chasm of death, through the familiar language of custom and protocol, the two sides are reaching for the forms of acknowledgment that should be enacted through the rites of mourning. This is the traditional function of funerary practices. The story implies that the Third Battalion’s purgatorial state is the direct result of their harried deaths in combat: no final prayers, no time for recognition, maybe not even a proper burial amid the bloody confusion of war.

It’s a conflict of unfulfilled obligation between the two sides. Under the gaze of those grim, lifeless faces, a peaceful resolution can’t be taken for granted. If the Living and the Dead are irreconcilable enemies, there are only two ways this standoff can end.

We can imagine how a less artful director—maybe an American like Zack Snyder—might have handled this same conflict:

One—the undead soldiers take their terrible revenge on the Lieutenant, using violence to carry out some form of cosmic justice.

Two—the Lieutenant restores the natural order of the material world by producing some awesome weapon from beneath his coat and blowing his former comrades away, cleaving a renewed separation between Life and Death in a hail of gunfire (preferably filmed in gratuitous slow motion over a heavy-metal soundtrack).

Instead, in a move that could seem maudlin to Western audiences, the narrative climax presents a moment of accord between the Living and the Dead.

The Lieutenant gives a passionate speech about the injustice suffered by the Third Battalion. He does his best to make amends. In a final gesture of official dignity, he calls his soldiers to attention and formally dismisses them.

This ritualized act of recognition is apparently enough to lift the curse, and reverse the metaphysical consequence of broken taboos. The undead soldiers make an about-face; the order is given to “return to base,” which presumably stands for some place of safety and rest, away from the front lines of the eternal battle in which they’ve been trapped. The Third Battalion marches away into the shadows.

The last survivor—and, by extension, the audience—is finally released from the confrontation.

Beyond the superficial distinctions between these two movies, there are some important differences in their conception (or are there?) that significantly affect their meaning.

As described by its very literal title—the vignettes in Kurosawa’s film were, reportedly, dramatizations of his own recurring dreams. A modern perspective sees this as a quaint personal touch from a beloved auteur. The reductive-materialist view of creativity treats dreams as a kind of psychological raw material, the unformed clay of an artist’s mind.

But these stories aren’t just vaguely “inspired by” by Kurosawa’s dreams, in a generalized way, as they would be in a more conventional piece of art. These are direct translations—which means the figures in the drama are, from the beginning, some kind of real. This puts the story in the realm of prophecy: a narrative from a mythic perspective that signifies a deeper metaphysical patterning.

The staging of “The Tunnel” reinforces this interpretation. The Lieutenant’s encounter with the undead Third Battalion is filmed mostly in static, wide-angle shots; the camera is positioned above the action, slightly to one side, as if the audience is watching quietly from a distance. It’s a very staged presentation that evokes the feeling of a theatrical play, which extends to the portrayal of the undead soldiers.

A Hollywood-style maximalist approach might have heightened the visceral trauma of combat deaths: ruined faces, bloody wounds, missing limbs, exposed entrails. When Dreams was made in 1990—two decades after Night of the Living Dead—these genre conventions were already well-established in global cinema. International horror movies like Tombs of the Blind Dead (1972) had picked up Romero’s ball (or decapitated head) and were eagerly running with it.

In fact, the standard had been set long before, at the beginning of the century. J’Accuse (1919) was filmed during World War I, and is now regarded as the first depiction of “zombies” on film. It shares many of the same themes as “The Tunnel”: thousands of dead soldiers rise from the battlefields of Verdun and march on a nearby town to confront the living. The film’s director, Abel Gance, famously cast real soldiers on leave from the still-active Western Front—many with fresh wounds and combat injuries—in the role of the Undead, graphically portraying the physical cost of war.

Foregoing the gory aesthetics of horror movies, Kurosawa drew on the relative minimalism of traditional Japanese theater. The undead soldiers in “The Tunnel” wear period-appropriate World War II uniforms, stained and tattered, to evoke the gritty realism that Romero’s movies pioneered. But this contrasts dramatically with the effects used for their otherworldly appearance: inspired by the kumadori stage makeup of kabuki theater, the revenants have lurid, pale-blue faces outlined with stark black shadows. The effect is powerfully eerie, while also deliberately preserving an aura of abstraction.

As a result, “The Tunnel” has the immediacy of a play: the focus is on the emotional-spiritual drama, rather than the visual aesthetics.

There’s a wider discussion to be had about the intersection of theatrical performance and spirituality. The specifics are largely outside the scope of this essay (and will be covered in the book). For now, let’s accept for the sake of argument that there are no easy distinctions between entertainment, aesthetic art, and metaphysical awareness.

The classical Greek concept of catharsis is significant here. While the modern (materialist) usage of the word has turned it into a purely psychological response, the ancient Greeks understood it as a form of spiritual transcendence—specifically in the context of theater. Cathartic plays were not performed for the viewers’ entertainment, or for the aesthetic appreciation of deep emotionality; under the right circumstances, they were vehicles that brought the human audience into direct contact with the numinous. These performances were more than just visual spectacles: they were ritualized invocations.

Seen in the right light, this confluence of prophetic dreams and invocational staging could—if we allowed it—suggest something of deeper significance than just a scary movie made by a famous director.

These are murky waters for a materialist understanding of creativity. Is there any evidence that Kurosawa made these choices deliberately? If asked, would he have said that he was making a visual representation of right relations between the Dead—the real, actual, eternally-present personhood of the deceased—and the Living?

Probably not.

There’s a very good chance that Kurosawa would say it was just an interesting idea for a movie. He decided to make it for the sake of art (and a bit of spending money). If pressed, being a poetic soul, he might well have been sympathetic to a Jungian interpretation: the figures from his dreams were archetypes from a deep well of collective human imagination, and while he had the means and the artistic vision to apprehend them—they weren’t really “his” inventions.

But from a mythic perspective, with an altogether different understanding of consciousness, we might still ask: could Kurosawa ever say with complete certainty what animated his ideas, and exactly why he chose to make what he did?

To a poet-priest in ancient Greece—or an Amazonian bruja, or a Sami shaman, or an Aboriginal cleverman—the facts of the case would likely seem self-evident, and maybe even unremarkable: a powerful man had a prophetic dream, which was sent to him by the Dead; he publicly dramatized it with the means at his disposal, in order to raise it as an issue of concern for the community. (And, in related news, thrown rocks fall to the ground, and the sun hides itself at night.)

Obviously, a famous film director would resist this interpretation: if the idea for a film was actually a message from the Dead, whose name gets written on the checks to be cashed?

And if a great romantic like Akira Kurosawa would balk at being seen as a prophet instead of an artiste—what would George Romero, a hard-nosed American kid from the Bronx, say about his own creations?

There’s no question of proving any of this to the satisfaction of skeptics. No forensic analysis of these artistic works will allow us to state definitively that the mythic interpretation is true and the materialist analysis is false. From the scientific point of view, this is all just speculative nonsense.

However—granting all that, it might still be useful to ask if we risk losing anything, as a culture and a civilization, by treating these things as done and dusted.

Myths have served as a regulatory mechanism throughout human history. They give people an evocative sense of relationality with the more-than-human world, and provide memorable examples of what happens when right relations are disrupted. When mythic stories lose their sense of metaphysical urgency—when they become simple campfire tales, or mundane entertainment—that regulatory mechanism breaks.

Reductive materialism sees myths as as a kind of proto-science: primitive humans had no explanation for the boom of thunder and the flash of lightning, and so they made up fanciful stories about giant cloud-people fighting battles in the sky with magic weapons.

Unfortunately, on top of being historically chauvinist, this interpretation is only half-true at best.

Elder cultures almost certainly had a better grasp of natural phenomena than modern caricatures allow5. What they didn’t have—at least, not in words that easily translated into English—was a conceptual framework for things like “ecosystem collapse” or “runaway militarism” Nor did they have the means (or the need) to write long-winded dissertations on the significance of these things.

What they did have were myths: marvels of interlocking symbolic narrative, portable and durable enough to survive for generations, to remind people of how the world fit together and how it might fall apart. These weren’t just time capsules, either. To properly recite a mythic tale was to call down the entities governing those timeless truths, and the eternal present in which they reside.

Within this larger mythic clockwork are prophecies, human-scaled narratives that describe how events in the material world align with the subtle patterning below the surface of reality.

A prophet, then, is someone who just can’t shake the feeling that something momentous is taking place—the first to feel the metaphysical rumblings that eventually erupt to the surface in the material world.

In ancient times, a prophet might have been the person shouting about omens and portents in the village square. Maybe they didn’t always have the right language to describe what they felt and saw. For whatever reason—throughout history, across cultures—the ones who get these messages always seem to be a bit touched to begin with, and often have trouble communicating sensibly with other people.

When these ancient prophecies were removed from their original context and translated into written texts—crucially, not something performed—they begin to look like fantastical stories. Visions of burning wheels within wheels, beasts with many heads, or the dead rising from their graves were filed away as folklore, or hallucinatory screeds.

Now, in the modern era, we don’t believe in omens. But these messages might still be coming through. Maybe a latterday prophet, with access to today’s tools, feels compelled to turn these visions into something like a movie.

Maybe, sometimes, they don’t fully understand why.

Pure speculation, admittedly.

Nevertheless—setting aside the specific mechanisms of these psychic eruptions, whether they’re Jungian archetypes or something even stranger—when these visions lose their metaphysical urgency, we lose a valuable counterbalance to human hubris.

In the mundane world, we have no trouble recognizing how dangerous it can be to lose perspective. Abusive and self-destructive behavior is partly motivated by an unwillingness or inability to take outsiders seriously. Anybody can invent reasons for needing one more bottle or one more hit—reasons for why the next tirade is unstoppable, life is unlivable, or yet another beating will help the recipient. This abuse is sustained by the perpetrator’s rejection of perspectives from those who aren’t suffering from the same delusions. We need outside voices to help us curb our worst impulses, which we’re all too capable of justifying to ourselves.

We understand this intuitively when it applies to everyday life. But in a secular, globalized, materialist culture, at a civilizational level—where do those outside perspectives come from? What are the voices we shouldn’t ignore?

For elder cultures, those voices spoke through myths and prophecies. The indeterminacy of these cultural forms was vital: in their original form, they didn’t have the rigidity of law—a limitation that would keep them from evolving with the culture. Raving street-preachers weren’t automatically elevated to the status of kings. There was always a sense that, at the end of the day, the translation of these messages were human contrivances, and would always reflect the fallibility of their interpreters.

However—that didn’t diminish the power of myths and prophecies to communicate profound truths under the right circumstances.

The organic conditions of performance (as opposed to recitation) connected an eternal mythic perspective with the material circumstances of a particular time and place. Human interpreters were open conduits, not sealed containers. Sometimes a familiar myth would hit the listeners with a strange resonance; sometimes the village lunatic would rattle off something so unnervingly correct as to warrant deeper inquiry. There was an understanding that the voices of the Eternal Outsiders could sometimes echo through imperfect vessels. And in a healthy society, those miraculous eruptions would motivate the community toward some determined soul-searching.

Are we really so confident that we’ve outgrown the need for those outside voices, now?

A mythic interpretation of the Zombie Apocalypse certainly points toward the relentless clanging of an unreceived message. In a very literal sense, in a very short time, the Reanimated Dead are suddenly everywhere in our culture. Attributing the feverish, memetic spread of these tropes to “just” aesthetic satisfaction or “just” cultural expediency is begging the question: what exactly makes these monsters so irresistible? What is so aesthetically satisfying about a cannibalistic, eviscerated, half-decayed human corpse?

Conversely, what does it say about our modern culture—our relationship with violence, and how we view our dead—that we can treat these grim figures as objects of fun?

We’d do well to remember that, originally, the word “monster” was inextricably linked to the concept of prophecy: the Latin monere means “to warn,” and monstrum was synonymous with “omen” or “portent.” The word itself is a relic of this same metaphysical imperative: when monsters appear, look around6. Seek out disruptions in relationality. Make sure you’re upholding your obligations. Renew your covenants with the more-than-human world, which will always have the power to immiserate you if left unattended.

Be warned.

Looking at these potential prophecies in this light—are we so sure that we have nothing to fear from the Dead? That they have no reason to condemn us, and no warnings to give?

Are we confident that we’re correctly interpreting these omens after screening them through the rationalist filters of metaphor and symbolism, instead of letting the Dead speak for themselves?

Are we treating modern-day prophecies with the urgency they demand, if they’re just the singular invention of a human creator—easily ignored, if they prove too troubling?

Look around at the world, and ask, even if it’s just for the sake of argument:

What do the Dead want from us?

This started well before Thing 2 was (temporarily, we hope) traumatized by accidentally wandering into a Walking Dead-themed FPS video game at the local arcade. Are we occasionally inattentive parents? Maybe. Should it be extremely disconcerting that first-person previews of dismembered corpses and splattering headshots are running continually on-screen, at a place that also features Pirate Mini-Golf? You be the judge. In any case—thanks a fucking bunch to the proprietors of Shipwreck Amusements for a memorable day.

The idea that texts within the horror genre are “just” symbolic representations is, for me, one of the strangest examples of materialist ontology eating its own tail: here is a genre where the supernatural is an accepted part of imaginal reality from the beginning—and yet mainstream analysts insist on disenchanting it, claiming that horror texts are only meaningful as a reflection of mundane fears. In fact—this disenchantment is a fundamental part of “fiction” as a concept. (I’m hoping to speak with

about this, an expert in both the horror genre and the epistemological weirdness of creativity.)As of this writing, “The Tunnel” is available in full on YouTube.

Western audiences might recognize this same phenomenon from The Sixth Sense, another contemporary entry in the corpus of prophetic movies.

While a full analysis is outside the scope of this essay, it’s worth noting: the idea that ancient people would blindly and fearfully equate something like thunder with a god— simply because they had no better explanation for it—is exactly the kind of reductive stupidity perpetrated by those who have never encountered an actual god before. Our ancestors almost certainly knew the difference.

Great stuff, the book appears to be cooking nicely!

Good stuff